The Science of Seeing

Today Dr. Josh Stout discusses the difference between perception and seeing. What begins as a mechanical process turns philosophical as our brain constantly interprets everything we see.

It's not what you see, it's what you think you see.

Please scroll down for links below the transcript. This is lightly edited AI generated transcript and there may be errors.

The Science of Seeing

Dr. Josh Stout 0:08

I definitely want to end up looking at the difference between perception and seeing, and that perception is something your brain does, but that we, you know, we see with our brain's perception.

Eric 0:25

I don't see with my eyes.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:27

Yeah, that's that's what we're going to talk about.

Eric 0:29

Okay.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:31

And yeah, yeah, it's exactly that.

Eric 0:34

Friday, May 3rd, this is episode three of season three. Hi, Josh.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:41

Hi, Eric. We're going to talk today about the science of seeing. I've been thinking about this for a long time. It's what I teach my freshman biology labs. And I try and not just emphasize the mechanics of seeing, but so they start to understand what they're doing when they see and see it as a almost philosophical activity, which is how I see it, that we interpret everything around us all the time, particularly with our vision. And it is physical.

Eric 1:17

Objects, not just experiences, not just interactions with people, but but the things and places.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:23

The things we see are not the things. And it's it's really to it to a tremendous extent. And seeing, I think, is the best example of it. All Our senses are like this, but our vision we take as facts, You know, what's in front of our eyes, and that's that's the closest we can get to these are facts, but nothing we see is a fact. So I start off with there's a lens in your eye that focuses the light onto your retina. That lens flips everything. Everything we see is upside down.

Eric 1:55

Yes, that's right. I do remember learning that.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:57

And it's not just upside down. And then our brain has naturally flipped it. Our brain is interpreting it and deciding which way it needs to go up in real time.

Eric 2:08

So there was an experiment where they put people in glasses. Yeah, exactly. And over time that was actually see things upside down anymore.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:16

This was actually Harvard students. My father was in the psychology department at Harvard. And so they talked about it and, you know, they experiment on everyone. Back then, there was no, like written consent. They didn't worry about stuff and they had a pretty good idea. It was going to work in rats. But they're like, Let's just try this on students. They hadn't tried this before. And so they put the they put a prism on on glasses and then let them walk around for a week with everything upside down.

Eric 2:49

Just makes me feel sick to my stomach just thinking about it.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:52

I suspect they were they were grad students, but I don't know it for sure. And so after a week everything had flipped back to normal again. But they must have had terrible headaches, bumped into stuff. I mean, just awful experience. Then they took the glasses off and everything was still upside down. And so they thought it would go back to normal, but they hoped it would and it did. So everything worked out fine, but it wasn't necessarily going to go that way. And so they walked around for a few more days with everything upside down, and then their brain reinterpreted to right side up.

Eric 3:22

Hoping, hoping, hoping.

Dr. Josh Stout 3:24

Right. So our brain is communicating with our eyes and then communicating with, say, with our inner ear so we know which way is up and try to make some sort of sense of the world. And so decides this is the way things are up, but it's absolutely done in real time. It is not a automatic relationship and we could easily decide it. Some other direction. There's there's no particular reason it has to be this way. It's just that, you know, all our ancestors decided it was the other way up, died.

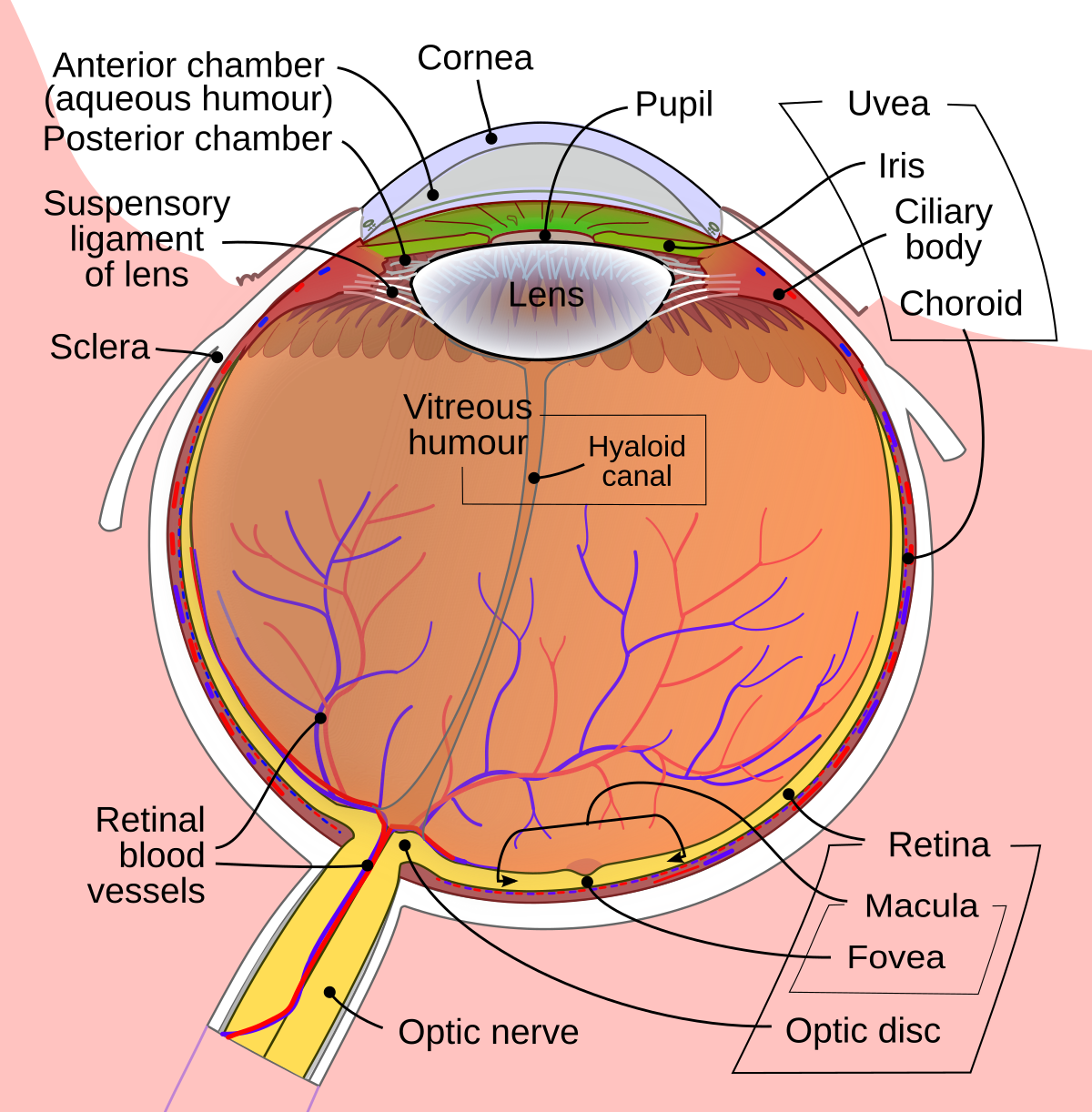

So this was something that was, you know, very early in the in the evolution of eyes, we figured out a way to get it so that it appeared right side up. But what I'm what I'm trying to say is it again is a real time interpretation that's happening. It is not something that is just automatically flipped. There's other things. So ah, the fovea, the the actual pit at the back of the eye where most color is absorbed is, is right at the center. And then there's less color as you move out from it so that by the time you get to the peripheral vision, we don't see color at all. You just think you do. There is no color in the outside of your peripheral vision. You're just imagining it and you're putting it there, but you don't actually see it.

Eric 4:40

I remember doing an experiment in high school. Was it high school? Was it junior high school where your partner would choose one of a number of colored pencils? And you look at a point and they would bring the pencil in to your field of vision until you could see the color. And if you really focused.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:00

If you really focus.

Eric 5:01

Really didn't move your eye, you couldn't tell for quite some time. You can find that spot.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:06

You can’t tell. And it's worse than that if you try and predict the color, you'll see the wrong color and you'll see it switch [Nice]. You can actually imagine the wrong color. I do with red and blue peas. Red and green pieces of paper. And I have done this. I have sat in front of a class holding the paper up where I can't see it. It's hard to set up, but I'm good at it now. And I'll say, I think that's red and I'll put it in front of my face and it's and it's green and it's 50/50. I don't know what it's going to be, but when I say I think it's red, I see red. I see the red paper there. It's it's really incredible how much interpretation there is. You know, there's also the blind spot. So where the optic nerve meets the retina, you know, a perfectly designed I would have a optic nerve coming to the back of a retina. But for whatever weird reason, our optic nerve goes through the retina and then connects to the front. So you can't see in that spot because there's an optic nerve in the way. And so when you shut one eye, there's actually a spot with zero vision, not not exactly in the center, but sort of in the lower right center, on your right eye, in the lower left center of your left eye. And you can't see anything there, but you can't tell that. And so normally each eye fills it in. But if you can close one eye, you're not missing a piece of your vision. It's but it's not there, I assure you. It's not there. And this is the fun part with my students, because I can actually demonstrate that to them. But you can watch things disappear.

Eric 6:33

And that's unnerving.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:36

It is unnerving. And yeah, because I have them look straight ahead and then they move a dot until the dot is just gone and it's really repeatable and they all get this one.

Eric 6:45

Yeah, I guess it's like the pencil experiment.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:48

It's hard with the pencil experiment. Students can't not look at the pencil when you move it or make a piece of paper.

Eric 6:54

Distinctly remember achieving it and being stunned.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:57

It's really, really difficult. My my favorite experiment of just super aware weirdness I read in Scientific American many years ago. It's called the Cheshire Cat Experiment. And this is what you do when you're left alone in a doctor's office and you're bored and they've left you with a mirror like one of those little hand mirrors of some sort. It's just, you know, one of the things on the shelf, you'll want to go through their drawers. They don't like that. But if they've left a little mirror on a shelf and you alone in an office, you don't know when they're coming back, you've got to do something with your time. So you take you take that mirror and you lie down on their on their lovely little bench there. And I have a hard time doing this. My home, my home is full of too many things in every directions. But doctor's offices are nice, they're relatively sparse, and they'll often have, say, like a cat poster over on one wall. And so what you do is you lie down flat and you get the mirror. So that one eye is looking at the cat poster and the other eye is looking straight up at the acoustic tile on the ceiling. Acoustic tile is perfect. It's got a faint pattern. So it will actually, you know, show up in your brain as a pattern, but it's not a very strong pattern. And so if you can hold still and you're not quivering, but you're really holding still and you're relaxed because you're bored in a doctor's office lying straight back and you're looking with one eye at a poster of a cat and another eye at the ceiling, the color and form of that poster will take over and both eyes will start seeing that cat. And you'll be seeing that cat very clearly with both eyes while staring straight up, because one eye is actually seeing through a mirror at the cat poster. And now here is the fun part.

Movement takes precedence over form and color. So you then wave your hand over the eye that's looking up at the acoustic tile. You'll actually see a wall of cat coming down and being erased by your hand and leaving only behind acoustic tile. So what you saw as Cat is now just being washed away, away, wiped away. And now both eyes are seeing acoustic tile. So so first both eyes we're seeing cat and now both eyes are seeing acoustic tile like that, except for the part that was focused directly on your phobia, the optical pit that really has the most sensors there. That part will still stay there. So if you're looking at the cat's eye or say its smile, you can see just the eye in the ceiling or just the smile.

Eric 9:33

So if you thought that the pencil experiment was difficult, this sounds like it was really difficult.

Dr. Josh Stout 9:39

I do not do this with my students. I explain it to them and explain what's going on, because it's a really interesting explanation of how your brain prioritizes color over lack of color form over lack of form, and then movement over everything. And you can see it happen. And then what you're focused on over even the movement, the very center. And it's it's super eerie if you do it with a person instead of a poster. So you can have someone sitting off to your left, say, while you're staring straight up. And if you look them right in the eye, when you wave down over the ceiling, their eye will be sitting in the middle of the ceiling, you know, blinking at you. A live eye. It’s the weirdest thing.

Eric 10:21

If they are perfectly still and you are perfectly still. I’ve done it.

Dr. Josh Stout 10:25

Yes, everyone has to be perfectly still.

Eric 10:27

How long does this generally take to take effect.

Dr. Josh Stout 10:32

Before both eyes get it,,, The problem is you're shaking your hand on the mirror. But if you can if you have a steady hand, it takes 30 seconds. It's really fast. It's it's easy to do once you get it. But getting it is super difficult.

Eric 10:44

It's kind of like, what are those things called the posters that you have to kind of.

Dr. Josh Stout 10:49

The magic eye. It's it's a little bit like that, but you're not you don't have to defocus you actually specifically focus on one spot.

Eric 10:55

But the point is that you have to control yourself in some way.

Dr. Josh Stout 10:58

You have to control the inputs, right? Because your body doesn't want you control your inputs, you want your eyes looking at all directions at all times, so nothing jumps out at you.

Eric 11:07

This brings to mind Carlos Castaneda somehow.

Dr. Josh Stout 11:10

Yeah, no, there's definitely, you know, doors of perception kind of stuff. You know, Scientific American at that time was very interested in how perception works and how our brain can be manipulated. They they they were they were, you know, in the 1970s, they were experiments where they were giving LSD to people and they called it wallpaper of the mind's eye. And then later articles, because you saw these colors and shapes behind behind your eyelids. And then there were later articles that talked about eye tiling, problems that created similar kinds of never repeating patterns that were always a little bit similar. And then we'll just come in this constant cascade. And it was a it was a basically a computer program, and they called it wallpaper, the mind's eye. And so they were very just interested in the way that randomness and form could organize themselves. And they were trying to look at it in a sort of very mechanistic way. It was it was it was an interesting way to see how their sort of editorial choices were looking at this for a long time. So I was influenced at an early age thinking about how we perceive the world and how it is it is warped by our, you know, experiences and our memories and the things around us. You know, we can't see the same colors in the same light. So you can turn up the light and down the light and you'll see different colors. So your reds will go away or the greens will come out. You know, that was one of the things that was supposed to happen during the eclipse when the greens are supposed to be super bright. And it didn't work for me, but depending on the your experience.

Eric 12:45

Or does this have anything to do with what color is the dress?

Dr. Josh Stout 12:48

Absolutely it does. So the background around the dress tells you what color the dress is. The dress is only one color. You can do it with a red pill green. But yes. Oh absolutely. That's the gold dress thing. Yeah. No, I have my students look that up. There's other versions of it. There is. There's a, there's a red one.

Eric 13:07

So you’re saying it has to do with what room you're in?

Dr. Josh Stout 13:08

Well that one has to do with the background around it. Whatever the background is around, the dress will dictate what the dress looks like.

Eric 13:15

But why did different people see it differently then way then, you know, if it's.

Dr. Josh Stout 13:18

Very at the edge. But most of that's going to have to do with your monitor and your color settings and the background settings and how it's set up.

Eric 13:26

And the lighting in your room and.

Dr. Josh Stout 13:28

Not if it's a coming from a monitor as much the light in your room isn't going to influence it, but the light you just experience before you looked at the monitor might if you were outside, everything is going to be uh…

To me, it looks blue. When I come in from outside, I start eliminating the reds and so that's going to shift the dress in one way or another because of that. So yes. Yeah, yeah. Your experience is absolutely.

Eric 13:53

Well, what's interesting is you're saying is you recover from these things within 30ish seconds.

Dr. Josh Stout 13:58

Well, I mean depending I mean you don't get good night vision for half an hour, 45 minutes. It does take some time to to to see things and stuff changes over the course of your life. I remember as a as a young child, when I would stare into a black room, I could see my, my, my, my cones, my color vision receptors firing randomly. And there was this sort of confetti of little tiny colors everywhere that's mostly gone now, you know, it faded and faded and faded and faded. And so, you know, my, my, my vision had been slowly turning down, essentially, that it was set a little bit too high when I was young, probably for the good, so that it sort of balances out as you get older and you start losing some of that random color sparkle in the dark room. Now there's sort of a very faint kind of pattern, but it's barely there, if at all. But when I was a kid, I it was very strong. I remember commenting to my parents about it and they're like, Yeah, yeah, yeah, that. But that's, you know, that's your actual cones just shooting directly into your brain and, and your optic nerve is actually an outgrowth of your brain. It is your brain. It's, it's, you know, brains evolved.

One of their major functions was to see things and so they had light receptors built directly onto light processors, and that was the brain. They had like two parts. You had the eyes and you had the nose parts. And the nose parts were just nose parts and the eye parts were just eyes parts. And they sort of made a bunch of lobes that organized themselves into a set of ganglia that could then control things like moving your legs. And that's this the centre of the brain, the basal ganglia, that that gives us our motion dark.

Eric 15:42

And does that smell like food?

Dr. Josh Stout 15:44

Yeah, basically. And then let's move our legs and run to it or thins or whatever it is that we're using to get there. But these are, these are how brains organized.

Eric 15:52

Oh, for when that was the most advanced sensory process.

Dr. Josh Stout 15:56

Well, I mean, we organized ourselves around the idea of sensory perception, and sensory perception was mostly organized around getting food or not getting eaten.

Eric 16:05

Right gives you a tremendous advantage.

Dr. Josh Stout 16:08

Absolutely. And you know what? Once you've evolved head heads, we're not things that evolved immediately. There were things that, you know, just were circles, like a jellyfish or blobs like like a sponge. But once you get a head moving forward, you put your mouth right next to your eyes and your nose right next to your eyes and your ears right there. And you just get everything in your head with your brain right next to it so that all those signals are super fast and you can bite things at the fastest, you could possibly bite them. And, you know, that's that's what heads are forward. We move head first. We know, like, that's why I bump into stuff all the time. But you move head first so that you're encountering the world with all those perceptions.

Eric 16:45

With your sensors.

Dr. Josh Stout 16:46

Yeah. And, you know, we, we, we have as primates evolved to see some colors that other other carnivores for example, can't necessarily see. So we get to see the reds that the dogs don't get to see and the cats don't get to see. They see very well in the blues, but we see fine and blues, but we get some of the reds probably to see the ripe fruit. I would have guessed a carnivore wanted to see blood. And we can do that. We're very good. We spot red. Really, really well. It shines to our brain. It releases dopamine very quickly. You like seeing it? It interests you.

Eric 17:27

That's why McDonald's and Burger King use red.

Dr. Josh Stout 17:28

Oh, absolutely. Red is red. Yeah. Red is important. It means there's blood that which means you can track it. It means there's ripe fruit. It means, you know, and, you know, our ancestors co-evolved essentially with flowering plants. So the fruit is designed to attract our attention. It evolved to attract vertebrate attention. And, you know, in some cases, primate attention.

We've been around for a significant portion as primates, not as people, but a significant portion of of the time that flowering plants have been around. They only evolved during the late Cretaceous. And, you know, we evolved as primates. You know what really seemed like 50 million years ago, I think maybe primates were starting or things that were just about to be primates. So, you know, there were mammals before that, but pretty early on. So of the 70 million years or so of or 75 million years of flowering plants, we've been here for about 50 of them. So our relationship with colors is is programmed into us by the plants. They would not have survived if they couldn't get us to do what they wanted. So all of these relationships are programmed into the brain, but also but also updated all the time so that we we can change in, you know, in real time how we're perceiving things related to the lighting in the room or our experiences or what we're expecting. We're talking about that with the with the colored pencils.

All of these things are constantly changing the way we perceive the world. There are there are portions in the brain called the the striated cortex that actually measure our lines vertical or our lines horizontal. And it's a it's a hardwired set of of of neurons that correspond to this one corresponding to vertical lines. This one corresponds to horizontal lines. And then all the other lines in between. And I know I worked with a professor at SUNY Albany who I didn't want to continue working with them because I realized what he was up to, which he would he would put kittens in these amazingly cute little sunglasses that only had vertical or horizontal oil stripes in them. And by the time the cat was, you know, something like eight weeks old, it could only see vertically or horizontally. It couldn't see the other direction. And you could you you could demonstrate this by you could have food in a thing that was horizontal and the one that could only see vertical couldn't see the food and if you gave it, you know, food in a in a vertical one, it could see it. So you could you could demonstrate that it literally could not see the horizontal stuff. And then he would open up their brains and look to see that they were actually missing those neurons. Those neurons had been removed. They would have had them as at birth. A lot of the brain's development is not growing new things but deleting things. And so cats in particular are very good at deleting their neurons to fit their somewhat larger evolved brains into a smaller package for their domestic kitten variety. They actually had slightly bigger brains.

Eric 20:48

But part of this experiment that you went very quickly by was opening up their heads and examining their brain.

Dr. Josh Stout 20:53

Yeah, you got to do some bad things to kittens. Yeah. And that's, that's, that's where we sort of parted ways. And, you know, I got, like, fascinating stuff. I guess I'm glad someone did this because now we know some things We didn't used to know those things. Yeah, but it's only a step away from the thing with the Harvard students. So you're like, I hope this all works out. You know, it doesn't.

Eric 21:12

We'll just open up your brains and see what happens.

Dr. Josh Stout 21:14

Yeah, exactly. But he so he couldn't. He couldn't open up a human brains. And it was. Yes, you know, it was even even by the eighties they'd figured out or I guess it was in the nineties by then they figured out that, you know, you probably can't do this to people in any way. So what they did is they compared American students from SUNY Albany with students from Beijing Normal University in Beijing and saw what kind of angles of lines they could see. And it turned out that…

Eric 21:46

I’m sure that that showed a measurable difference.

Dr. Josh Stout 21:49

It did. Because the Chinese students were able to see more degrees of detail and they think it's because of their written language. Our written language is all ups and downs and sideways and they have many more angles. And so they could actually see angles at more precision than we could.

Eric 22:05

And they also have to memorize a lot more.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:09

It's not the memorization, it's just the physical act of seeing.

Eric 22:12

But but what they have to see, they have to see so much more. Each character is unique.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:16

And it matters. So their brain, their brain is going to essentially upregulate the differentiation between very tiny.

Eric 22:25

So it can be recognized quickly.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:27

So it can be recognized quickly. Exactly. Because it doesn't matter to us in the same way. And so this is what I mean by it's it's done in real time. There are long lasting effects. Those are real neurons that are being grown or deleted and edited in, you know, all the time. But it's something where the culture has now changed their their physical ability to see. And so this is how we we start to need to think about how our expectations and our culture actually change what we see, because we see with our brains, not with our eyes. That was sort of where I was going from the beginning and we can ignore what's in front of our eyes if our culture tells us not to see it. You know, we're very good at seeing what we want to see and hearing what we want to hear. And this this this is a real problem. And I think that science actually does offer a system for learning how to physically see reality that I think is is in many ways better than other other ways of looking. Artists look closely at things. They look at meaning in a way. Sometimes scientists don't look. And I think that's important. But actually, just seeing what is real is a lot of what scientists spend their time doing. And it takes practice.

Eric 23:44

But if you divorce that from meaning you end up with. Oppenheimer.

Dr. Josh Stout 23:48

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. There's there's issues to it. But I'm just talking about being able to literally see what's in front of your eyes.

Eric 23:56

But even science has been many times in history, co-opted to the point where what's in front of your eyes is.

Dr. Josh Stout 24:04

Okay, so I'm talking about looking through a microscope, looking through a telescope. So this definitely happened when I oh, I can't remember his name offhand. The guy who has got lots of towns named after him in New England,

sorry, was looking through a telescope and saw the canals on Mars.

That was a case where his preconceptions were deciding what it was that he could see. And he very clearly saw these canals at Mars on Mars. And, you know, for a while other scientists are seeing those canals on Mars. And then I.

Eric 24:44

Am.

Dr. Josh Stout 24:47

And then it was it was. Yeah, Eric just found the chaparral canals. I was actually thinking of of of the American astronomer and New England name just can't quite anyway they were, they were expecting to see it. Yeah. Lowell. Percival Lowell. Yeah exactly. Exactly. Lowell Massachusetts was a lot of thinking and they were expecting what they would see and they saw it but they, but other scientists weren't able to replicate it. And so when they were seeing with clear eyes there were no canals there. And so then eventually everyone stopped seeing the canals. Reality actually worked because of the way scientists learn to look at things. It is a little bit easier. You know, we talked about this last week. Scientists were absolutely behind racism for a long time, but eventually they realized it just wasn't true at a fundamental level, it didn't exist and wasn't a thing because race doesn't exist. It's not that racism doesn't exist, but the race doesn't exist. And so they they no longer went with this false thing they were seeing, you know, everyone had done the group think, you know, everyone had seen the same thing, but they were able to move away from that. And it's something that I really think is important in our in our in our modern culture is that we need to learn how to see. And it's something I train my my students to do. It's it's really difficult to see through a microscope. There's lots of shadows. There's lots of specks. You see your own eyelashes and to know what's eyelash and what's, you know, an actual paramecium swimming by that takes a little practice understanding what's a drop of water or a bubble that they're seeing these the all of these things take practice take take imagination. I have to imagine what it is I could be seeing. It was one of the earliest, really best trainings I had was not just, okay, so now you know how to use a microscope. How do you understand what you're seeing? A microscope takes basically two dimensional slices of a three dimensional world. And so one of the early exercises was looking at something that had been sectioned into slices and then trying to build a model of it in my mind by looking at the slices in a microscope. And once you can do that, you can do things like focusing up and down through something and seeing the slices yourself, and then you start to understand things three dimensional shape. It's very difficult to teach this to students. I can I can get them to see through a microscope. Some of them begin to understand, you know, in a general way what's eyelash and what's sample bite. But I don't think most of my students can reconstruct three dimensional objects in their brains the way they would need to. And once you can do that, once you can really construct something like that, then you have the ability to see the specimen more clearly. It actually shows up better because now your brain is understanding what it's seeing. There's been there's been a fair amount of stuff with this. And in language and language perception where if you know the words someone's going to say, you can hear it even with a lot of static. But if you don't know what those words are with there's a lot of static. You can't hear anything at all. It's just gibberish. But once, you know ahead of time what it is they're going to say, that same recorded statement is perfectly clear.

Eric 28:29

I think we've all had the experience of looking at a looking at something, looking at an image and having no idea what we're looking at until somebody says, Oh, don't you see the. And then the whole thing comes together. Yes. And suddenly you understand it.

Dr. Josh Stout 28:43

Yeah, No, that happens to me all the time.

Eric 28:44

But I also had I had I had a the director of of the technical director of the theater at Sarah Lawrence College Lance Miller had I remember this must have been freshman year took us out on a sunny day in the in the spring and said or was it the fall doesn't matter was a sunny sunny day warm up to go outside and he said look at the bricks What color are they? And we said, they're red. Yeah. And he kept asking us questions. He kept prompting us until we were seeing a million colors in those bricks. We were seeing completely different things than we had been seeing just 10 minutes before. Yeah, it was it was a phenomenal experience. And it you know, it's like you're saying once you can see you can't stop seeing it.

Dr. Josh Stout 29:28

No. And it's it's it's really important. And I, I first learned how to do this while working with microscopes and thinking about microscopes. It certainly applies to other things out there. But then once I understood that this was going on in my brain, I started trying to train myself all the time to be able to see properly. So, for example, you know, there's fun things you can do. You go out, look at a night sky when it's nice and dark out and you find the Pleiades. So the Pleiades is a little constellation sitting on Taurus is back. So you find Orion and there's a little view of Taurus facing Orion. And then there's this little sort of almost miniature Big Dipper just behind the, the horns of, of, of, of Taurus. And then you try and count the stars. This one is really super difficult and weird. You can't see the seven stars, but there are seven stars there.

Eric 30:23

You have to look away from it.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:24

You have to look away from them. And there's actually more than seven stars there. If you use a telescope, it's a it's a large cluster of stars. Most of the time you can see sort of a blur if it's if it's, you know, too much light pollution. But the darker and darker it is, the more you can see. But you can never quite get to to all seven unless you're not quite looking at them. Why would that be? Because the center of our our vision is the color vision. And the peripheral vision has much better black and white and movement. But every time you look at it, it disappears. Every time you look away, it'll it'll come back again. So it's it's constant interpretation of the world and trying to trying to recognize when you've seen something is difficult and believing what you see. And is it is it the canals on Mars? Is it an artifact? Is it just your imagination? Or did you really see that thing believing?

Eric 31:20

What you see is absolutely, completely effortless until that first time that you realize that you weren't seeing what you thought you were seeing, and then how do you ever become confident again? Like…

Dr. Josh Stout 31:34

Well, you have to have this doubt and you have to check it. You have to do it again. And and but there's it's it's not just the ability to see some things. It's it's noticing as well. So about four or five years ago there was a major fungal infection of the trees in in New Jersey. In New York they had the tops of the trees were dying everywhere. No one talked about this anywhere. I was noticing it because I would drive along the highways. Highways are stressful on trees and it was maybe one in 15 trees was badly infected. The whole top was was, was, was dying. And you could look off into the distance on the hills. And they weren't quite as common as they were on the highways. But you could see it all the way across the hills. And so on long car trips, I consider this a nice sort of longitudinal sample of what the forests were looking like. And I was getting really, really worried and I started going online. There was no one writing about it. No one was even thinking about this stuff. I finally found one discussion group of the I think it was it was it was one of the state environmental groups like the DC, something like that, that that, you know, they have people on the ground whose job this is. And they were saying, Are you seeing this? Yeah, I'm seeing this. Huh. Don't know what it is. And that was the end of that. No one sampled it. It just went away.

Eric 32:57

It did go away?

Dr. Josh Stout 32:59

Maybe it didn't kill everything. We still have trees. Yeah, but it could have happened at any moment that it turned into this pandemic. Of all the trees, it was mostly affecting maples, which I. You know, that's a lot of them. But it was it was affecting a lot of trees in a lot of regions. And it could have gone the other direction. I lost some trees. It might have been coincidence. There's more than one fungal disease out there that kills trees. I lost some cherry trees. That was probably something they call fire blight. It's a it's another fungus. But there's all these weird reared creatures out there that if you pay attention, you will see a new organism several times a month that you have never seen in your life. You will see birds you've never seen. Every year you will see insects you've never seen every week. If you look really, really closely, any time you look hard, you will see something you've never seen before. You know, as a kid, I used to just lie down in the grass and watch the things crawling on the grass. My eyes aren't that good anymore, you know, I used to be able to see something laying eggs and see the individual eggs, and I could see the shape of them, so I could see how different things had, different shaped eggs and that kind of stuff. I can't see that it's all dots to me now. But, you know, at the time it was like having a microscope, fries, and I could just really see all of the details and so I really have tried to learn how to not ignore the stuff I see, You know, recently one of the more bizarre moments is I was looking at the trees around my house in Stillwater, and there were these things that looked like orange jellyfish in the trees and on the ground like and I touch them and they were they were basically like jelly with tentacles like, like, like a whoosh ball made of actual jelly, like orange, bright orange, tend to crush ball looking things on the trees everywhere and on the ground. I'd never seen this in my entire life and it turned out to be the spawning portion of a fungus that lives in cedar trees but has a complex life cycle. So when it puts off the spores, it's the thing that makes those sort of brown fuzzy spots on your apples. And it's an apple rust disease. It also makes brown fuzzy spots on the apple tree leaves. And so your apples need to be sprayed to keep them perfectly green with no with no spots on them. It's not dangerous for you. I've eaten non sprayed apples with those rusty spots them. They're not a big problem. They, they have a slight noticeable texture as you bite them through the skin but they don't change the apple at all. If it gets out of control, it can kill the apple trees. So the same sort of stable fungal relationship can definitely get out of control. I think that's what was happening with these maple trees. So it could have been global warming, changing, changing the temperatures or changing the increased rainfall, or it could have just been a random outbreak that just happened. It could have been part of a more complex life cycle. This thing with the apple trees, everyone knows about it, but most people go I mean, in terms of the scientists who study this sort of thing, but in terms of regular people going through their lives, no one has ever heard this. I brought pictures into my department of biology professors and no one had ever seen this. I showed it to farmers who grow apple trees and they're like, Oh, yeah, apple rust, cedar, apple rust. I know all about that, you know? So there are people who need to pay attention, but you could go your whole life and never notice that there was these bright orange, tentacled kush balls in the trees all around you. It's really easy to do. There's there's stuff like this going on all the time. You know, there is there is something I didn't notice until, you know, relatively recently, you know, now I notice it all the time. And my kids do because I pointed it out to them. There are there are aphid species that make waxy secretions. So instead of just pooping out sugar water for ants to eat that, that's a different whole different thing. Like ants will actually farm aphids, which you can also notice, like look for ants and aphids. You'll see them doing it and they'll make this whole layered puffball of protective waxy stuff around them on a tree limb. And so if you're walking through the forest, you look down, you'll see sort of a little bit of black stuff on the leaves. If you look up, you'll see what looks like a tree with fur on it. And if you go near that tree with fur, the tree will start. The fur will start to move because the aphids are actually wiggling all of these long filaments to try to scare you away. And it is eerie and strange and I now see it every year. But it took me it took me 40 years to see it. And there's stuff like that everywhere. And, you know, I'm sure someone out there saying, Yeah, I've known that since I was a kid, but other people are saying, what exactly? And so there are things like this all around us all the time where we're not paying attention, we're not seeing it because we think everything is normal. And normal is a lot stranger than you think it is. And I you know, there's there's dangers to it. And, you know, we put people into into pigeonholes. We see them the way we want to see them. You know, this is a lot of the things behind racism. You know, you you everything that confirms your biases, that's what you see. If something doesn't confirm your biases, you don't see it. So there is there's there's really this interplay where we think what we see is reality. But what our eyes do is just the beginning of a large scale set of interpretations that we can literally not see things that are right in front of our face and we can see things for the first time that have always been there. There there is, you know, there is beauty and strangeness all around us that we are not noticing. And I just wanted to put this out there. It is something you can actively learn how to do. You don't have to be a scientist to do this. All you have to do is pay attention. When you see something and it looks a little odd, don't just go and let that drop out of your mind. See it? You know, notice what that just was. You might never see that again. That might be the one and only time you get to see thing.

Eric 39:21

I would, I would put to you that Yeah. With some effort you can certainly see things that you haven't seen before no doubt. But I also would say that, you know, the things that have learned to see came from, you know, teachers. I've been the fact that I can teach myself to see things came from teachers who were teaching me how to see.

Dr. Josh Stout 39:44

Sure. Yeah, absolutely. And that's that's that's part of human culture, you know, learning how to see stuff. And I once asked asked a tracker, how did you learn to do this? And he had some help. But after after he'd gone beyond what his teachers could show him, Right. He had to do things like he would make a footprint and then he would watch the water trickle into the footprint and see how long it took. He'd look at the little bits of mud and see how long they took to dry. And just hearing him tell me that, I started thinking about footprints and I started looking at them in a different way and I was able to see footprints and I could tell you how roughly how old they were. And then I started thinking about it the way a tracker would look. And I could see was it pushed down a little bit in front? Was it accelerating? Was that thing running away? What was it running away from? Why it running way? Was there a bunch of them running together as a herd? Could I find another track related to it? All of those kinds of things. Now, now that I've seen that these these footprints are is there going to be a bent branch somewhere? Can I can I look where something is broken? Is there is there a leaf that's been turned over? And when you see a leaf that's been turned over, if it's moist on the underside, we know where it's been turned over there. That underside is now upside. That's going to dry out very, very quickly. So you can tell how the time tell when something's been bumped by. So, yes, it definitely was a teacher that taught me how to do it. But he also taught me how to teach myself how to do it.

Eric 41:08

Yes.

Dr. Josh Stout 41:09

And that's sort of what I'm trying to say right now is, is we should be teaching ourselves how to do things. And, you know, certainly we need to do it in politics. I think we we hear what we want to hear and see what we want to see in politics. And this is dangerous and this is, you know, how so many lies are spreading to the world. But we've talked about that. I don't need to talk about that right now. We'll probably talk about it again later. But I wanted to talk about it as as a essentially physical art, Like, you know, listening to music, you you learn how to appreciate music by someone teaching about the music, but also by paying attention to the music. And the same thing is is true for for for visual seeing that it's important for art to have people show you what things are. But then when they do think about, Why didn't I see this before? How is it that they're seeing it and how can I make myself see in the future.

Eric 42:00

I mean, what you're saying is, is don't just think about the thing that you're seeing, but think about yourself.

Dr. Josh Stout 42:07

Think about yourself. Absolutely. Yeah, absolutely. And why is this appearing this way to me right now?

Eric 42:14

Why am I feeling this way about this thing? Why does something feel off or why does something feel wrong? Yeah, why is this Why do I want to look at this more?

Dr. Josh Stout 42:21

Yes. Speaking of feeling off, you know, the uncanny valley with humans when they started trying to animate humans. We're really good at noticing faces. We have hardwired facial receptors that tell us, you know, what people's other people's emotions are, because we need to know those things. And that's hardwired in our brain. So when we see a fake animated person that's too close to a human, it makes us feel very bad. You know, we we see those as alien and they must be killed, you know, whatever that is. I don't like it.

Eric 42:50

It makes me terribly uncomfortable in a profound way.

Dr. Josh Stout 42:53

Yeah, it's like a walking lie. Yeah.

Eric 42:56

Yeah. Interesting.

Dr. Josh Stout 42:58

Anyway, I just want to. I just wanted to put that out there as. As. As a way of thinking about the world where you can see more than you do. All of us all the time. It's not like you snap suddenly and get. It's something you need to do all the time.

Eric 43:13

And something we need to learn and relearn.

Dr. Josh Stout 43:16

Learn and relearn. Exactly. And in every field. And if you meet someone from another field who can show you something you've never seen before, talk to them about that. Ask them about that. How is it you see that? What? What? What do you look for that shows you what you are now showing me?

Eric 43:31

Yes. I get this from my kids all the time where they they they tell me that they're seeing something. And my instinct is to say, no, that's not there, but I have to check myself and I have to say, well, they are actually capable of seeing things. I'm not.

Dr. Josh Stout 43:46

Oh, absolutely. Yeah.

Eric 43:48

Talk to them and find out. Maybe I could see this.

Dr. Josh Stout 43:51

Yeah. Yeah. Okay.

Eric 43:53

Well, thank you, Josh. Thank you, Eric. All right, folks, until next time.

Theme Music

Theme music by

sirobosi frawstakwa