The Paleolithic and Neolithic for Kids

In three short episodes, Dr. Josh Stout lays a foundation and shows artifacts revealing fascinating details about our stone-age relatives.

Please click here for the transcript of Paleolithic for Kids Part 1

Please click here for the transcript of Paleolithic for Kids Part 2

Please click here for the transcript of Neolithic for Kids

Please click here for Links for Further Study

Below are lightly edited AI generated transcripts of each episode. As these are AI generated, there may be errors. Please scroll down for links below the transcript.

The Paleolithic for Kids Part 1

Eric:Welcome, everyone, to MindBodyEvolution. Thanks for joining us. This is the Paleolithic for Kids Edition, Part 1. Everybody, this is Dr. Josh Stout.

Dr. Josh Stout:Hello. Hello. Hello. I'm really excited to do this. I love thinking about human evolution. I love talking about the story of how we got to where we are. And I wanted to explain what the Paleolithic is. So, literally,

Dr. Josh Stout:the Paleolithic is old stones. And I have a whole bunch of old stones over here.

Dr. Josh Stout:Some of them are probably over a million years old, a fantastically long period of time.

Dr. Josh Stout:If you think about all of human history, it's about 6,000 years old at most. So several times that. And we're going to go all the way back to 6 million years ago when we were living in the jungle, basically as chimpanzees.

Dr. Josh Stout:So chimpanzees living in the jungle, suddenly the earth starts to dry out around 6 million years ago when we move into the Serengeti, into the grasslands. And we, uh, we evolve bipedalism so that we can move around more efficiently, so we can look up over the grass. Uh, but that's pretty much our life. We are, we're basically bipedal chimps. We have, you know, these little tiny heads. I mean, smarter than your dog or your cat, but not as smart as, as a modern human.

Eric:Bipedal

Eric:meaning?

Dr. Josh Stout:Two legs. Y. Yeah. Yeah. Sorry. Uh, so

Dr. Josh Stout:we're walking around on two legs out on the Serengeti and frees up our hands. Uh, we're mostly eating roots. We're, we're, we're, um, pounding on stuff with sticks and with rocks, but we're not making tools as such. Uh, and this goes on for, you know, three and a half million years. Pretty much always the same. We're getting a little bit better at walking on two legs. Maybe our brains are ever so slightly bigger, but not much. Our teeth are really big for crushing stuff.

Dr. Josh Stout:And then suddenly around two and a half million years ago, um, we get stone tools and this changes everything. Our brains double in size. We become smarter. Uh, and

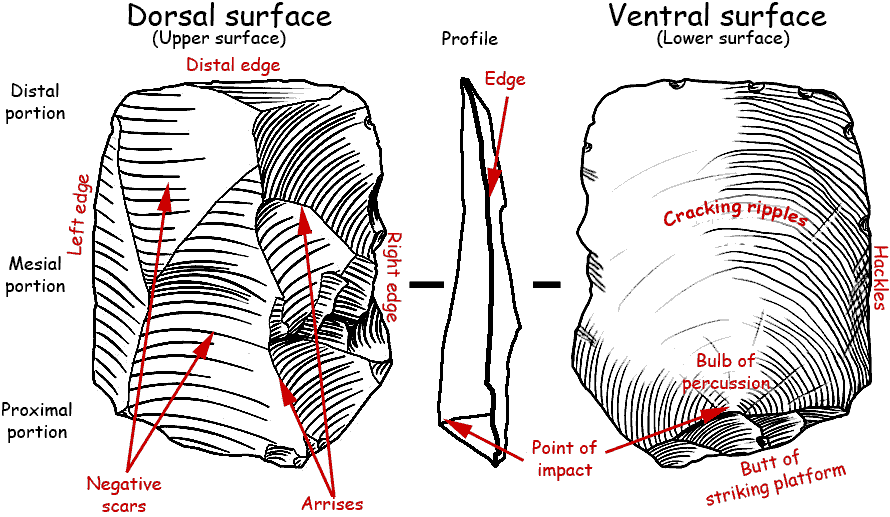

Dr. Josh Stout:it's probably because we're able to suddenly walk over here, go over here and make a stone tool. Uh, and now we can, if we see a, um, if we see a dead carcass, uh, out on the Serengeti, we can run over to it with our bipedal gate and we can slice it open with our new, uh, sharp stone tool. Uh, and these were very simple. This was sort of least effort technology, just a couple of chips out of a piece. They didn't even all look the same. Some of them were different than others. So they came in, uh, a variety of just sort of sharp with a round part that you could hold. And

Dr. Josh Stout:these would get you digging through a carcass. And so, uh, uh, we were, uh, um, able to, uh, now run over to a carcass, use our hands to throw some things awkwardly at, uh, uh, other things like a hyena or a lion that might be there.

So a bunch of us were all screaming at the lions and hyenas, the lions and hyenas will leave. We can slice open the carcass. And this is a new source of food to feed our giant brains and our giant brains allows us to make these tools.

Dr. Josh Stout:So it's the sort of feedback loop between the, uh, the giant brain and the tools and the tools and the giant brain. But then there was a problem.

Dr. Josh Stout:We're able to get the food, but now we have other competitors, us. And so now we have to fight against ourselves. And it was a major, major change at this time. We went from being short with thick fingers for using tools and a big, big brain for making tools to much, much taller with a shoulder and a, uh, elbow that could really throw and a whole body could turn. We became taller. Our waist became supple and throwing became our main ability. So it wasn't throwing first. It was smart first, but throwing was the next thing we did. So it went bipeds walking on two legs, then being smart, then throwing.

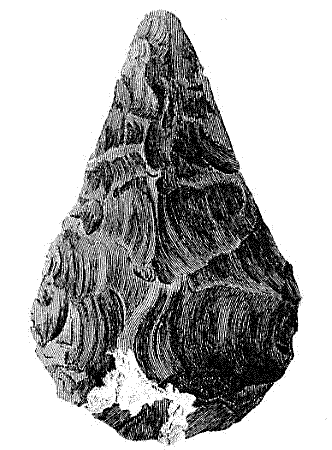

Dr. Josh Stout:What did we throw? And why did we throw it? We were throwing these things. These are hand axes. Uh, and we held my think by the tip and we were throwing these things. Uh, so these things are, um, sharp all the way around. Sort of like a ninja throwing star. There's no dull area, but you could still hold them pretty well.

Dr. Josh Stout:And they would make a nice sort of Swiss army knife for slicing for stabbing into something. Uh, but I think the key, uh, innovation was throwing these and these lasted for. for 2 million years technology. These are, these are hand axes, but they don't really have a great definition or a great, um, a way of describing them. Uh, you know, some of them are really big. So this would've been great for, you know, crushing into say an entire elephant bone. You would've been able to get the bone marrow out of that to feed your big brain. Uh, some of them were smaller, but still, you know, really, really old. And they often have these, these pointy tips. And I think that that's what allowed us to get a really good spin on them, uh, for throwing them.

Eric:You get really close and show that tip

Dr. Josh Stout:for throwing them at each other. Yeah. So this is a very pointy, very thin tip.

Dr. Josh Stout:Uh, if you're making a stone tool, this is hard to make, I can make a least effort tool. Uh, just a couple of chips. I've got a sharp knife. I can, I can slice something, but something like this. It takes some skill to keep that, uh, point there. It take, it takes a little bit of work. Uh, and so then this went on for maybe two million years. We're just making these hand axes. Some of them we make kind of pretty. We'll have, we'll have stripes on them.

Eric:So they meant, they meant to do that. You think those stripes were there?

Dr. Josh Stout:Yeah. I mean, they found a rock with stripes on it and said, that's a pretty rock. Uh, we, we, we, we really liked some of these, uh, these, these prettier ones.

Eric:But what you're saying is that they're not entirely, they're not completely utilitarian, that they were also objects that were understood as, as, as beautiful when they made them.

Dr. Josh Stout:We liked stripes. They were completely utilitarian in that sense. We were not, um, I don't think we were picking rocks that were bad tools that happen to have stripes. We were picking the best tools we could. And if they had stripes, we'd incorporate them into the shape of the stone and into the way it worked so that we, we, we really liked, uh, the, the, the, the decoration, but we weren't going to be decorating things. We liked the way things looked aesthetically. And that sort of kept going for a

Dr. Josh Stout:while. Our brains were slowly getting bigger. Every time they got bigger, we got better at throwing. We got a little more food. So our brains could get a little bit bigger. The competition against other humans for these carcasses was starting to improve. At some point we're starting to get fire. We can get more calories out of it. Um, all of these things are, are sort of building along.

Eric:Why

Eric:can we get more calories with fire?

Dr. Josh Stout:Oh, fire because you cook things. You can break it down. It's easier to digest. Uh,

Dr. Josh Stout:and we get to sort of the end of this, uh, lower Paleolithic, and the hand axes get smaller. They get closer, finer, finer, finer work on it, thin sharp edges, still has this point for throwing, but this is a much more finely worked tool. There's a nice little thing here. Um, and this might well have been for scraping against a stick because we're getting closer to where we start getting spears. We certainly would have had pointed sticks by then. Uh, and we could have maybe thrown them. Uh, the sticks didn't last, but we got a variety of tools. They didn't all look the same. Uh, some of them were, uh, this would have been more like a drill. So we're getting to the end of the, of the, um, lower Paleolithic about, um, say 300,000 years ago. So still really, really long, but we've gone through over 2 million years of time. Uh,

Eric:2 million years when we were making just these.

Dr. Josh Stout:Just one thing in one, in one way

Eric:and making these things better and better

Dr. Josh Stout:and making these things better and better.

Dr. Josh Stout:And, uh, addition to spears, what defines the, um, the, uh, the middle Paleolithic are, are these things called cores. And so this is a stone core, prismatic core. And you can see that this was several flat faces and this was used to make tools. So you would make a prismatic core and then you get more flakes off of it. So this became a more efficient way to make tools. Or

Eric:a core, meaning

Dr. Josh Stout:of stone. You start off with a round stone and you made it into this square shape. It's a square shape of

Eric:something and you use it to take pieces off.

Dr. Josh Stout:And the pieces are then your tool. Um, one of the kinds of cores that get made at this time, uh, looks like a turtle looks sort of like back of a turtle here. Uh, this is still a hand axe, but the hand axe itself was a core. And you can see the whole back here was a flake that was taken off. And so this would have been flake after flake after flake from this prepared, uh, level. Uh, core looking like a turtle. And this was a, you know, beautiful piece, uh, from North Africa there.

Dr. Josh Stout:Um, as core technology improved, uh, we're getting smarter and we get to the end of the, um, we get to the end of, uh, the first wave of humans. And we're now into archaic humans where now our brains are really as large as they are today. Uh, and we're moving into the next wave of, of the, uh, of moving past the, the middle paleolithic into the upper paleolithic. And that'll be a part two that we're looking at. And in part two, we're going to see things much more emphasizing these cores. So we're going to see much, many more things, uh, that, uh, use this kind of preparation. Uh, and things are going to be getting finer and finer.

Dr. Josh Stout:And I just wanted to end this last piece showing almost the whole paleolithic in a single piece. single piece. This would have originally been a very old hand axe, and then sitting out on the desert, it got darker and darker. This would have been maybe its original outside of the stone, sitting here out on the surface. You can see these darker areas, but this is a slightly lighter one. So this was younger than this piece. So this may be a million years ago, maybe 500,000 years ago, and then maybe as recently as 150,000 years ago, this last portion here. So this was all the same stone.

Eric:So, you mean this is a core that was used over maybe 700?

Dr. Josh Stout:Well, it was a series of tools. It started out as a big tool and got smaller and smaller as new tools got used, made out of it. This was actually found by a mercenary in Oman that I bought the things from, and he'd been wandering deep into the desert in a forbidden area and came out with a whole collection that I was able to get. And I just sort of wanted to show you that the sense of history that you could drop a tool and 100,000 years later, pick it up and rework it into a tool, drop it again, and another 100,000 years later, get made into a tool again. Just history was so long and so huge at that time. All right, that's the end of part one and two. I will go into part three when we're talking about the upper paleolithic. And we'll see even more finely worked tools.

Eric:All right, folks, tune in for the next episode. Thanks so much. Take care.

Dr. Josh Stout:Thank you so much.

The Paleolithic for Kids Part 2

Eric:Folks, welcome back. Mind, Body, Evolution. This is Paleolithic for Kids, Part Two, and once again, Dr. Josh Stout.

Dr. Josh Stout:Hi. Uh, we just covered the, uh, lower and middle Paleolithic, and now we're going into

Dr. Josh Stout:the upper Paleolithic. And at this point, uh, you know, our brains have been getting bigger and bigger. They're as big as they're ever gonna get. And now we're getting into sort of the, uh, the end game between the archaic humans.

Dr. Josh Stout:So there's archaic humans in Europe, the Neanderthals. There's archaic humans in Africa, Homo sapiens. And they're going to run into each other. The first couple times, Neanderthal wins, Homo sapiens stays in Africa. Next time, Neanderthal loses, Homo sapiens takes over, uh, all of Europe and Asia, also stays in Africa. And then this is sort of where we end up, and there's only Homo sapiens left. Before that, we had a big bushy family tree of lots of different directions. After Homo sapiens arrives, it's pretty much just us.

Eric:Wait,

Eric:so what happened to all the, what happened to the Neanderthals?

Dr. Josh Stout:We got really, really good tools. And so we were able to out hunt them, out compete them. If we fought them, we would probably win the fight. But as much of that, we were, we were eating the food right out from under them. We also interbred with them. So we have some Neanderthal in us today. We had some of the best friends that we had in the world. But the key thing were these, uh,

Dr. Josh Stout:these cores, which I was showing last time. You can see how this is, this is a nice piece. Uh, you know, you can see how it was arranged. This would have made lots of new tools from it. But the cores became really refined.

Dr. Josh Stout:obsidian needle from Central America. And this shows what a core could be. This is a core. And so each one of these little things was a single blade worked off of this obsidian needle. And so this would have enabled really, r fine pieces.

Dr. Josh Stout:So you could have scrapers. So this scraper is a single chip off of a core. This is one big chip. And then there was one more chip taken off of it. So this was done very, very quickly. First you had to prepare the core, but then you had a tool pretty much ready to go in just a couple of moves. And so this would have been a very good scraper. There were other more refined pieces.

Dr. Josh Stout:So some of these would be very long and thin. This took a lot of work. This was almost like a sickle. So you could harvest grain with it. You can see this curved edge here. Also would have been useful for first scraping and in general preparing hides and pieces of wood.

Eric:So are they called hand axes even if they don't have that tear drop shape?

Dr. Josh Stout:No, no, no.

Dr. Josh Stout:We're way past hand axes now. Now we're talking about much more refined tools. Starting in the middle Paleolithic, we started putting tips on spears. Those aren't hand axes. Those are spear points. And so now we're talking about either spear points or defined tools that had specific uses like a scraper or the spearheads or the awls or things like that, that are much more defined. We started seeing that happen in the middle Paleolithic. We saw,

Dr. Josh Stout:we saw some of these, these pointier, awl like tools that you could have been scraping. That was a much more dedicated tool.

Dr. Josh Stout:But now by the, by the upper Paleolithic, we're getting to things that are really, really refined. So

Dr. Josh Stout:these very, very thin spear points, this would have been from North Africa. This is the kind of thing that would have let us win against the Neanderthals. You can see this designed end here that would have fit onto the, onto the spear. You can see the chips along the side here. Now this is done an entirely different way. Before that you had to take a, to make a rock sharp, you just hit it with another rock. Now we're taking a stick, putting it exactly where you want it, and then tapping on the end of the stick. So you can get these tiny, tiny little chips all along the edge here. Making it really, really beautiful.

Eric:That is a really refined piece of work.

Dr. Josh Stout:Absolutely.

Eric:Compared to what you were showing in the first episode.

Dr. Josh Stout:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Here, here. We'll compare the two.

Eric:It's entirely different. It's fascinating.

Dr. Josh Stout:Look

Dr. Josh Stout:at the refinements between giant chips out of a big stone versus tiny, tiny, tiny little pieces out of a much more

Eric:and then we're, we're, we're still, we're still working in stone. It's still a lithic-

Dr. Josh Stout:Still absolutely the Paleolithic. Right. We haven't gotten to the Neolithic at all. This is still the Ice Age.

Eric:Finding rocks. Yeah. And we're making them into things, but what we can do with them is amazing.

Dr. Josh Stout:Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout:This is all happening during the Ice Age, from, from the beginning, from two and a half, a million years ago, right to- through the Upper Paleolithic. We're now talking about 60,000 years ago, leaving, some of us leaving Africa, 50,000 years ago, the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic in Europe. And these, these technologies are getting better and better. The points get thinner. They get longer. They get more refined. They have to be worked more carefully. Some of them, you can see each chip comes off in a parallel to the next chip. Each one is, is tiny. So you'd get, you know, six chips just out of your, your pinky nail. So this is, this is very, very fine work. It allowed us to hunt very large animals. These spear points could go right through a mammoths hide. We could, we could take over a cave from, from a cave bear. We could fight the cave lions. The, this was a technology that allowed us to expand across the world, uh, and have new resources. Uh, we were, we were working on things like thread. Imagine what thread does for you. You can sew some cloth. You can, you can build clothes for yourself. You can move into ice age Europe when it's really, really cold. You had fire in Africa, but now you can build clothes for yourself. Think about what else thread can do for you. You can have a fishing hook. Imagine a fishing hook.

Dr. Josh Stout:That's the key imagination. For a fishing hook, you have to imagine a fish in the water. You have to imagine what that fish is going to want to eat. You have to have, um, a way to attach that fishing hook to you. So even because of long, thin line, maybe on a stick. And you have to have a way to like, like, really hold that fish in place when you went, once you catch it. So all of these things involve much, much more forward thinking planning.

Dr. Josh Stout:So even though Neanderthals, um, had big brains, as big as ours today, we were able to out think them for resources, for territory. And eventually, uh, we, we, we took over and basically got rid of them.

Eric:Out thought them, but we didn't have bigger brains. So how did we manage to out think them?

Dr. Josh Stout:Out thought them, uh, because of changes in the way our language genes worked, uh, allowing for abstract thought. We definitely had language. We definitely had some way of communicating before that, but something in Homo sapiens, back in South Africa, probably changed the way we think about, uh, the world around us.

Dr. Josh Stout:And so at the same time, we're getting these advanced tools, we're getting art at the same time. And so we're painting on the sides of these cave walls. We're, we're, we're, we're, we're thinking in abstract ways. And we're able to make more and more refined tools. Eventually you get a bow and arrow. Imagine what that is. You had to make a string. You have to have a stick attached to a stone. You have to have understand how an arching piece of stick works so that you can then shoot that arrow somewhere. Uh, so this was a, a whole new level of technology, uh, from the, uh, the upper paleolithic. Uh, this was a time when we were, we were rapidly coming up with new tool after new tool and expanding into whole new areas. Uh, and so this is setting us up for the end of the ice age where we can get the next level of human civilization, moving into things like farming, moving into things like making a boat so you can get to an Island, whole new ways of living that we hadn't had before.

Eric:But you're saying that the change that allowed us to go from making the big clunky stone tools to the very, very, very fine stone tools came at the same time with the development of art and, and things that were different in the way that we think in a lot of came together

Dr. Josh Stout:in a lot of ways. art is like the evidence we have of, of language. And so art suddenly starts appearing.

Dr. Josh Stout:Yeah, the Neanderthals had some very, very, uh, you know, rough bits of art in sort of earlier in, uh, earlier at this, during this time, but it was after they had probably interbred with us. I think they had our genes, even though they wiped us out. Uh, and so I think they were able to, um, do pretty well for a while. They, they, they coexisted with us for, for a good period of time, partly by taking some of our genes, understanding some of our technologies. They got better spear points. They got better art. Uh, and they probably had better language, but they still weren't able to outcompete us. We got some good things from them as well. We got, we got, uh, some of their immune system. Uh, we, we, uh, much of our, uh, uh, uh, the people who, who left Africa got some of our skin and hair from them. Uh, we didn't get everything, but we got small pieces of their genome that we inherited from them because they were useful in these, in these cold environments. Uh, you know, having very pale, uh, uh, skin might've been useful in Ice Age Europe, uh, to, uh, allow us to get more sun, uh, so we could get vitamin D. Um, having, uh, thicker hair might've kept us warmer. So these were the kinds of things that we got from the Neanderthals. Um, we already had big brains and we didn't want any of their brains. So we didn't take their language genes. The, uh, language genes we evolved in Africa were better. We were smarter in Africa, so we didn't want any of that part, uh, from the Neanderthals. We just sort of took the outside that was, uh, uh, evolved for their, that, that, that, that European cold world. And, uh, so, uh, as we moved in, uh, we, we replaced them, but we also interbred with them and took some of their genes with us that we could use. But, uh, yeah. So we, we, we covered the globe at this point for, for most of, uh, Asia and Europe and Africa, and it was with these new technologies, but it was really led by imagination. The ability to imagine a fish, to imagine, uh, I need to sew something. How am I going to do that? I need a needle. Uh, I need to attach a needle to a thread. I need to put an eye in a needle, put a piece of thread through that. How am I going to make a needle that small? All of these kinds of questions were things we were solving at this time, using our improved language, which we could then teach. Once you have language, you can teach the next generation. If you figured out a fish you can show someone else how to make a fish hook. So this, this was our next thing setting us up for, for leaving the caves and, uh, entering the, the, the Neolithic.

Eric:All right. Where are we going next episode?

Dr. Josh Stout:Neolithic. Right. Right into the end of the ice age.

Eric:All right. All right, folks. Well, thanks very much for listening. Mind body evolution. Tune in for episode three. Thanks everyone. Three. Thanks, everyone.

Dr. Josh Stout:All right. See you next time.

The Neolithic for Kids

Eric:Starting over here in this camera mind, body evolution, this is the Neolithic for kids. And everyone, this is Dr. Josh Stout.

Dr. Josh Stout:Hi.

Dr. Josh Stout:Good to see everyone. Um, so

Dr. Josh Stout:we were talking about the Paleolithic- old stones. Now we're gonna talk about the Neolithic, the new stones. And so this is a period when the ice age is finishing, the climate is much more stable, and people are starting to develop things like, they're gonna move into agriculture. They're gonna, uh, start learning how to dig in the ground and plant stuff. They're gonna learn how to, uh, make a dugout canoe, chop down trees. Do things that involve a lot of hitting and whacking your stone into something else. And, uh, look at- think about how we've been making stones prior to this.

Dr. Josh Stout:Before this, if you wanted to make a stone tool, you took a stone and you chipped it. And you chipped it to make your new stone tool. So you had something that was designed to be chipped. It was sharp. It would cut through an animal very nicely, but it wouldn't dig. What would happen if you took a chippable stone tool and tried to whack it into the ground and use it like a shovel? You'd chip the stone tool. And so we couldn't use the stones we'd been using anymore. We needed to use a new kind of stone. And so we started using things closer to jade, stuff that just wouldn't break and couldn't be chipped. But now you've got another problem. You've got a stone that can't be chipped. How do you use that as a tool? How do you make it into anything? All of our technology was how to make beautiful, beautiful stone chipped tools.

Dr. Josh Stout:So the next stage is taking these big pieces of jade and turning them into this.

Dr. Josh Stout:So this is not chipped this is ground. So this is known as a Celt and this was actually from Papua New Guinea, you know, within a hundred years of today. So this is the Neolithic really survived for a very long time. And this is the number one tool of the Neolithic. These jade axes that were found everywhere. If it wasn't jade, it was a stone like jade, it was going to be very hard, difficult to chip. And this gave you an edge that you could use for grinding against wood, for chopping something. You could use it for harrowing or digging. And all of this would have been mounted on a longer piece of wood. So you had this, this larger thing like an ads that would, could be used for scraping or chopping.

Eric:But you're saying that this type of work actually would not be possible with the stones that they were using in the Paleolithic?

Dr. Josh Stout:No, no. If you'd, if you'd, if you'd tried to chop a, you know, if I'd taken this and I tried to break a tree with it, where, where it's chipping now would just chip more. And so the stone would have just broken. So we needed to find stones that didn't break that, uh, were, were really resistant to chipping.

Eric:Ah, and that's why they needed to be ground.

Dr. Josh Stout:That's how they, why they, because you couldn't make a stone by using chipping. It was, it was really

Dr. Josh Stout:difficult. So how would you make something like this? Uh, it was, uh, first you take a, a boulder and you heat it. So piece would crack off and then you'd have a piece that was cracked off and you could maybe pound at it. So you can't chip it, but if you whack at it enough, little pieces will come off. And so that was called pecking and you'd sort of peck away at it, like a bird pecking at something. And you'd peck away at the shape. Uh, and you could also take a piece of string and go back and forth. And how are you going to cut a, cut a stone with a piece of string? You put a bunch of sand there. And you can imagine that would take a really long time taking string past sand to cut your way through stone. Very, very long time. The string keeps wearing away. You have to get another string and another string and another string.

Eric:But, but that works. That actually works.

Dr. Josh Stout:Eventually. So the, the, something like this might've taken two years to make. Um, not all of your day, but it was mostly sort of the old men of the village. They'd go down, sit by a stream and just sit there scrubbing the stone against the side of the rocks on the stream to make it more and more and more polished. And over two years, you would get something like this. So these were incredibly valuable. These became sources for, um, trade back and forth. And so some of them, uh, really had, you know, just spectacular manufacturing.

Dr. Josh Stout:I don't know if I can show you how this works, but you can see, there's the edge of the jade right there and you can see the light shining through the jade and the black is magnetite. And then there's, there's the green jade that you can see when I shine my light through it.

Eric:Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout:Yeah. And,

Dr. Josh Stout:uh, so these became trade items as well. So something like this, you could have trade for, you know, half a dozen goats or, uh, maybe a wife, uh, that, that, that was the kind of, uh, things that were traded back and forth. And so these wide trade networks were being developed. Uh, jade axes were found in England. There's no jade in England where they were coming from the Swiss Alps. And so they are traded over very long distances to have these things being produced. Um, we also saw things, uh, like

Dr. Josh Stout:this, this is a bracelet from North Africa made of stone. You can see on, on, on the underside here where it was all sort of chipped into, into place. So that was just hammering through something. Once you've got a sort of thin piece of stone, you just whack it until you've got a hole through there. Uh, and then you just rub it until it's, uh, this nice ground stone, uh, all the way around. So once we figured out how to smooth stones, this became a new way to make art. And there were more tools, uh, being made from this.

Dr. Josh Stout:Some of them, we don't even know what they are. So this was, uh, from the Americas, um, probably a loom weight. So if you have a string hanging down like this, the strings altogether would be for weaving a blanket.

Eric:Is there a groove right around the top?

Dr. Josh Stout:There's a very thin groove right around the top there.

Eric:That's fascinating.

Dr. Josh Stout:But it wouldn't have been a fishing weight. It wouldn't have held on very well.

Dr. Josh Stout:Whereas something very similar looking, this was probably for personal decoration. Went through the lip, right through here, and would have been sticking out just like this. So, uh, this thing also ground into shape. This is a nice piece of crystal quartz, uh, and was for human decoration. So there were things that were new tools that we, you know, hadn't been able to make before. Now we've got new kinds of decoration, trade items like that, that bracelet.

Dr. Josh Stout:Uh, and we get into, uh, new kinds of weapons as well. So this is a, um, this is a mace from, uh, Costa Rica. And you can see it's got this sort of hammer side here, a hole to put the stick through. Um, and then if you look at it, this is actually a, um, this is actually a, uh, a vampire bat. And you can see the nose and the teeth of the vampire bat and the ears coming up.

Dr. Josh Stout:And so you could imagine that, uh, much of the conflict, uh, at this point would have been ritual, uh, involving, um, uh, fighting for not just territory, but some sort of, uh, needing to have, uh, sacrifices or, or bloodletting. And you could imagine a mace that looks like a vampire bat. You can imagine it's getting some blood. And, and so they're making the fields fertile, uh, through these battles, uh, through these conflicts. Um, but if you look at this, this would have been a fearsome weapon. But at the same time, if I'd ever used it, the, uh, the ears would have broken off. This little nose would have broken off. So at the same time as, uh, uh, having actual physical power, there was the idea that things would also, um, be ceremonial. And so at the same time as, uh, the, the, you know, warfare is developing and, uh, we have, we have the development of, uh, farming. We also have the development of ceremonial centers, uh, things like Stonehenge. Uh, in the Americas, you have these giant ceremonial centers with the, uh, huge, uh, pyramids. And so in addition to, uh, pure military power, there's also sort of a psychological power. And the more beautiful you make something, the finer, the carving, the more influence it has on someone.

Dr. Josh Stout:So even if you have a mace that is a weapon, it's also a tool to show how, how, how great you are. You spent all of this time, not just to make a round thing to hit someone with, but to make something beautiful and to make something, uh, that would, that would show your inherent power. Um, many of these, these jade axes, uh, were not just, uh, for, for, um, uh, doing something like farming or making a dugout canoe, but they were also, as I mentioned for trade and for showing your personal, um, uh, uh, uh, worth that you had this thing that had been made out of really nice jade. And so very often, if you look at the edge there, it hasn't been used much. There's not a lot of chips there. So, uh, these pieces, while they might be used other times, they wouldn't be used at all. They were just to show your power. Uh, so for example, the jade axes, um, sometimes, uh, on burial would get broken deliberately to show that we've now sacrificed this spirit and it is no longer a part of it. Or they would be very carefully kept whole and left next to the person who was buried to, uh, help them in the afterlife, to give them, uh, something valuable to show, to show their importance. Uh, so all of these things we're developing are ideas of, of, of farming, of, uh, of ritual, of, uh, of life after death, of, uh, making beautiful art, of, uh, uh, governments and how you project power, you project power through wealth, through trade, through the ability to show what you can do. Uh, and so all of these things are very, very much part of the Neolithic.

Dr. Josh Stout:And I just wanted to show one fun little piece. Um, not everything in the Neolithic was chipped. Also was the power of the bow. And so this is a beautiful little crystal arrowhead, tiny, tiny little thing. Um, and so this was from, uh, uh, uh, South Carolina. I found this myself. Um, this would have been perfect for, uh, hunting, small animal, small game. And this, uh, was another part of the Neolithic was the, uh, development of the bow, uh, and widespread use of the bow. So now this, this is a, a new technology that has spread and allowing us to hunt in new ways. And it became the center of our warfare as well, that we were, we had, we had the ability to make an army of people all shooting the bow at the same time. And so this projected the power of the king and the priests and a way of, of, uh, actually controlling large areas.

Dr. Josh Stout:Because once you have farming, you have to defend your land. You can't just leave. As a hunter-gatherer, if someone tried to invade, you just get up and go. But as a farmer, you have to stay there. So you need to defend that land. You need to have maybe a castle or some sort of walled fort. You need a whole bunch of people who are able to defend it working together. Probably not full-time to get a, you know, a full-time standing army would take a lot of money. So these are people who are probably farmers most of their lives. But some parts of the year, they would be able to, uh, actually go and either invade somewhere else, expand their territory, have more areas to farm, uh, or defend against, uh, people who are trying to take their land. And so this was also definitely part of, uh, of, of human development and human history is a projection of power. And really with farming, we have the, um, both we, we, we have something to lose and something to gain. You can gain territory. You can go and steal someone else's wheat, right? If they've stored all their grain for the winter that they've harvested in the fall, now is a really good time to run and get it. You're not farming anymore. It's winter time. They have the food all stored up. So now there's something to go to war for. And so this, this is a whole new world we've moved into from individual small groups of hunter gatherers, chipping little stone tools into shape to now grinding them into these, these, uh, much more formal kind of things, doing much more formal art, huge societies with kings and, and priests and, and armies going and fighting each other for territory and, uh, and resources.

Dr. Josh Stout:So that's finishing the Neolithic. It's basically everything from the end of, of, of the, uh, ice age up until really, uh, we start using metals. So, so beginning of the bronze age, but in many ways, until today, there, they're, there, there's still, uh, Neolithic societies that only recently, uh, have started using, uh, metal axis, for example. So like those, those, these, these, um, these new Guinea jade axes were only made maybe a hundred years ago.

All right. So that is the, the, the Neolithic.

Eric:And that completes our cycle on the Neolithic and the Paleolithic for kids.

Eric:Folks visit mindbodyevolution. info. Thanks so much for watching. Thank you so much. Thank you, Dr. Josh Stout. Thank you. Take care, everyone. See you soon.

Links for further study:

Theme Music

Theme music by

sirobosi frawstakwa