r/K- An Ecological Theory That Is Saving The World

Today Dr. Josh Stout discusses the evolutionary reason parenting styles are so different today than they were in the last century. Investing in our children is necessary in the modern cubical meritocracy, and keeping them in school is saving the world.

Don't judge yourself - understand your evolutionary context

Please scroll down for links below the transcript. This is lightly edited AI generated transcript and there may be errors.

Eric 0:02

Friday, December 1st. And this is the beginning of season two of mindbodyevolution. Hi, Josh.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:11

Hello, Eric. Yeah, very excited about this moving forward. We took a week off for Thanksgiving. I am going to be trying to work without notes this week because I have been putting together some grants, which I'm really excited about with the Life Worth Living project. We'll see if that works out. It's very.

Eric 0:28

Exciting.

Dr. Josh Stout 0:28

Very exciting. I've got a whole bunch of different projects happening. I'm getting my research class together, so we'll find out about that. I can give you some updates about that, probably probably in season three. Okay. Going to take some time. But today I want to talk about a ecological theory that is, you know, well known in academic circles, but not really outside of it. It's called R versus K sounds kind of obscure, but it actually explains how basically spoiling our children is going to save the world and how we we are driven to do things that seem to not necessarily be good for us or our children, but it is actually part of a larger force that evolution is has has has dictated for us the sort of ecological relationships have dictated for us. It's a lot like economics. Economics has a has a particular drive to it. And you can you can come up with equations that describe how things work in economics, but that once you understand it, you can see how everything else is is pushed by it. And it's not a it's not something you decide. It's just sort of a force of nature.

Eric 1:42

The thing that happens.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:43

A thing that happens. Exactly. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Eric 1:46

So R versus K.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:47

R versus K, exactly. So the R part is reproduction. And so organisms compete to produce the most babies. That's the nature of evolution. And so one way to win the evolution game is producing more babies. And so that's the the are competition. So if you are an organism that wants to produce babies, you have babies very early, you have lots of them. They're small and you don't give a lot of care to them because they have to be often making their own babies as soon as possible. So things that are what you call are selected are things like mice.

Eric 2:23

Cockroaches.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:24

Cockroaches, things that reproduce very, very quickly, have zero parental care. They tend to be small, short lived and have small brains. So they're just sort of the essence of of of what R selection is.

Eric 2:37

What is that R for, reproduction?

Dr. Josh Stout 2:39

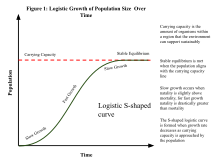

Reproduction, literally for reproduction. And then the the other side of it is K selection. K because of whatever reasons, people who are first working on this were Germans. They came up with K for carrying capacity.

Eric 2:52

Okay.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:52

It's just one of those things. Yeah.

Eric 2:53

As in, as in the, the.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:55

K means the carrying.

Eric 2:58

But what is carrying capacity?

Dr. Josh Stout 3:00

Okay. Yeah. We're about to talk about that. Okay. Yeah. So carrying capacity is the, the limits of a particular environment. So if you're an organism and you need to live in a hole, how many holes are there to live in? That's the carrying capacity in a particular environment. How much food is the environment is in the environment, are you going to able to support your offspring?

Eric 3:19

So in other words, how what population can the environment support?

Dr. Josh Stout 3:23

Right? And that would be theoretically a given number so that you can't really exceed that amount. And so if you're an organism living at carrying capacity, you're working very differently from one that is trying to compete at reproductive rate. So reproductive rate is when there is a few limiting resources. You're just trying to push out babies as fast as you possibly can and those babies are going to be pushing out their babies as fast as they can, etc. But as the numbers build up, you start to reach a maximum level in that kind of world, when there is some sort of limiting factor, usually whoever's biggest and strongest wins, not the one with the most babies. So if you think of something like an elephant, an elephant has very few natural predators. They have the limits of their own habitat, are limiting their population. They have little slowing them down. Of course, obviously modern humans have slowed elephants down greatly, but before us, elephants really had nothing that they had to worry about. They had very large babies that they would give a lot of parental care to. They would teach them where to go, where to find the foods, and they would protect those babies. So those babies had a very good chance of surviving. And when they did, they would become a huge animal that had nothing that could threaten them. And so what they want to do is they want to make the biggest possible baby. And if you want to make the biggest possible baby, you don't have lots of babies. You have one baby at a time and you make it really, really big. And the biggest baby is going to be the biggest elephant and it's going to win the elephant game and make new big babies. And so this is carrying competing, carrying capacity. So it's very, very different. It's almost the opposite of competing for reproduction. So you have babies later in your life after you've built up resources and you have more experience, you put all of your resources into your baby to make them as big as possible so they can grow up to be the biggest possible elephant. You tend to be long lived because it takes a while to make a baby, and if you're going make more than one, it's going to take a really long time. You have very long gestation period so that the baby's developing for a really long time. And then when it's born, you have further care after that. So a lot of parental care, a lot of communal care. It's not just one female elephant with a baby elephant. It's the entire community working together.

Eric 5:39

The creatures are born, running, and the creatures need years.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:44

Of years and years of care. Exactly. And this care has has a real value because as as they they as the elephant develops, it learns its culture and its culture tells them where the water is, tells them where to go at a particular time, and they're able to travel around their habitat and understand it in a way that if they hadn't been taught, they wouldn't know it. Many, many of these societies tend to have a longer lived matriarch. That is the sort of repository of knowledge this goes for pretty much all of the the more intelligent species out there, like whales and elephants. They tend to have a group led by an older female who has the sort of knowledge of the group and tells people where to go and what to do, not people elephants. But the the idea is that the knowledge itself is part of the ecological adaptation, that this knowledge contained in the community, in the culture, is vital to raising this young elephant. And the by keeping this knowledge in the in the group, the young elephant has a much higher chance of success and will be a bigger elephant that then makes more bigger elephants. And so this is a is a is a evolutionary strategy as opposed to our selection that maximizes things in a totally different direction. Big brains, large body, long lived, lots of parental care. So obviously humans are lying in this realm. We are not mice, we are much more like elephants. And this is true of mammals in general. If you compare, say, mammals to insects, mammals in general tend to have more infant care. We nurse our babies. It's one of our defining characteristics. We tend to work in social groups in sex can as well, but it's very, very different. And so this this is a defining characteristic of our entire group in general. But then when you get into primates, it becomes stronger. So primates tend to have more parental care and fewer babies than other comparative sized animals, and they tend to be a little bit smarter. So they're they're have slightly larger brains. They're spending more time training, they're young, where to find food, and they are basically competing with other members of their own species. Usually primates are going to have within species competition. There's also between species competition. But a lot of it is is going to be within species, Primates in general are going to be smarter and have more parental care. So as primates developed, they tended to get larger body sizes. So so lemurs in general are a little bit smaller than monkeys. Monkeys in general are a little bit smaller than apes. So obviously there's exceptions to this. There's tiny monkeys and there's bigger lemurs. But as you look at the entire sort of graph of body size and sort of evolutionary development.

Eric 8:53

As you look at the graph of body size of humans in the modern era, we've gotten bigger.

Dr. Josh Stout 8:57

How we we can talk about that. Okay, that's a separate issue.

Eric 9:01

I don't mean to jump ahead.

Dr. Josh Stout 9:02

Yeah. So in general, we've been moving in this direction longer lives, larger body size, bigger brains, more parental care and more competing at carrying capacity. So you can see that that monkeys are smarter than lemurs and they have a longer parental care, period. Apes are smarter than monkeys and they have an even longer parental care period within this group. Except for gorillas, we're really the largest in humans are the only thing larger than us would be, you know, a silverback gorilla, which are huge, but they're also our closest relative. So they're definitely the direction we've been moving in for for, for, for some time. Once you get up to something like a silverback gorilla, you really have eliminated almost all of the predators that can that can compete with you as the.

Eric 9:55

Elephant of this.

Dr. Josh Stout 9:57

Yeah, exactly. And it's all about guarding mates and making sure you're the one to reproduce. If you're a female silverback, you want to protect that silverback. You're a female gorilla. You want to make really big babies so one of them can grow up to be the dominant silverback and have all the reproductive success. And so it becomes even more important because it's somewhat of a winner take all if your male baby doesn't win this this this contest to be the big silverback with a harem, he's going to have zero reproductive success because he'll he'll never have a reproductive opportunity. Whereas a silverback that has a harem of females has all of the reproductive abilities. So there's even more pressure to produce really large babies that are going to win these competitions with humans. We ended up in a in a similar sort of situation. So we we left the jungle, we became upright apes on the Serengeti, and our brains grew maybe a little tiny bit. We probably were needing a little bit more tool use because we had to dig up tubers. It's really hard to dig with your hair, but if you have a stick, you can dig something up. So I'm not saying we were intelligent yet as we're going on the Serengeti, but we're needing some of the aspects of intelligence so we could dig up a tuber with a stick, We could crack a nut with it, with a with a rock, some very, very simple tool. Use the kind of things that you would expect a chimpanzee to be able to do if it, say, were a biped with hands, that it could hold things with a little bit better. And being out on the Serengeti, but still mostly chimpanzee hands, mostly chimpanzee brain, but just sort of a biped that needs a little bit more than what chimpanzees needed because they need to know where things are. It's harder to find a tube underground than it is to see a fruit growing in a tree. So knowledge would have been useful to pass on to future generations. So we could imagine that these these early Australopithecines would have lived in family groups. An isolated female australopithecine with a young child would not have been able to survive on her own. So we could imagine that this would have built a community much like the whales and the elephants. They probably had some older female which knew where things were, and that was would have been, you know, guiding the organization with the sort of cultural memory of where foods were, where the rains come, that kind of thing, dates, times, places. When we make the transition to genus homo, when our brains roughly double in size, we become even more dependent. So when when, when, when an infinite is born, we can't make our brains big enough to be as intelligent as we are today. That's sort of a confusing way to put it, but I, an infant, must be born with a brain small enough to get out of the birth canal of a biped. If you spread the hips any wider, the biped waddle side to side. Pregnant women have problems with moving side to side as they walk anyway because their hips are spreading and this is slowing them down. It's making them less efficient. Any further spreading of the hips would be even more inefficient. So bipeds are strictly restricted to the size of the birth canal, which restricts the size of the brain. So we maximize the size of a brain of a baby that can be born. And then we end up with essentially a 21 month gestation period. So we have the first nine months in the womb, and then we continue after that for about another year of a brain growing. And so this is.

Eric 13:34

The skull plates are not fused.

Dr. Josh Stout 13:36

The skull plates are not fused, the neurons are dividing rapidly. The the brain is growing really rapidly. And so the the these infants are even more dependent than any other primate has ever been. So primates in general are smart with big brains and dependent infants. But now we've we've entered a whole new range of dependency. So we're k selected. But on another level that other things really haven't been in terms of our dependent offspring, we take so much effort to raise our young.

Eric 14:07

And this this happened during the transition to the Serengeti?

Dr. Josh Stout 14:13

The Serengeti was really just us becoming upright apes. This was the transition to us getting big brains, the our genus. So Serengeti was about 6 million years ago. Our genus is about 2 million years ago. Okay, so now we have not just sticks and stones that we used to dig something up with, but we have stones that are purposely shaped. They have sharp edges, they take chips and they require a little bit more work. They require a plan ahead of time.

Eric 14:41

So this was well after we got access to the marrow. When you were talking about this is that moment. This is them.

Dr. Josh Stout 14:46

This is that moment. Australopithecines probably were doing some scavenging. They would have been able to maybe scare off some predators by doing some throwing, but now we're at a whole other level. Australopithecines would not have had a shoulder that could throw wood very well, just like chimp chimps can't do that. Homo Erectus has a I even better body for, say, running. But specifically it has adaptations to the the shoulders that allow throwing.

Eric 15:14

So we've reached the point where we have actually been selected for better body is for throwing and running.

Dr. Josh Stout 15:22

Right. And in terms of our our our, our brains up until now, keeping a small brain worked really well with being a biped because you could easily give birth. But now you've reached something else. We've reached a period where our our abilities are requiring large brains to make these sophisticated tools to do the kind of planning and throwing and targeting that I think we need to do is Homo erectus needs a really, really big brain. And so once we start producing these big brained offspring, we require even more parental care. We require more sharing within a group. So the groups are forming a sort of higher level culture where individuals can no longer survive on their own. Even small family groups cannot survive on their own. They must be interacting with others. Interestingly, you see the sexual dimorphism between males and females reducing during this period. So Australopithecines are more like a silverback gorilla. The males are almost twice as big as the females, but that by the time you get to Homo Erectus, the males are only about 20% bigger than the than the females. It's it's it's it's closer to a chimpanzee kind of size disparity. So there is still male male competition, but it's within a larger group. So the same way chimpanzees are all working within a larger group and because of that can have a much larger troop than, say, silverback gorillas. So silverback gorillas might have 20 in an entire group, whereas a chimpanzee could have 80 or 90 with an entire group because they have many males working together. The same thing would have been happening with Homo Erectus. So once males are now cooperating, they don't need to have one that's twice the size of everyone else. They're now much closer in size to the females. Probably tools have something to do with this. If you've got a rock in your hand, it doesn't help you that much to be twice the size of the other guy, so size doesn't matter as much. Our teeth get smaller, Our our sexual dimorphism shrinks at the same time as our brain is doubling in size. This would have been very, very difficult for women going through childbirth because now essentially the brain and birth canal are the same size or the brain is actually slightly larger. So the hips have to shift to give birth. The brain has to be squeezed to actually come out of that. It actually has to fold the hinges in the in the in the skull. So these are very dependent offspring now. But during this dependent period now is arriving another level of culture. So these stone tools can be taught to the next generation. You can learn to do these things that get you more food. So now instead of just a crushing rock that you maybe could pound through a bone through to get the bone marrow, now we have slicing and crushing rock so we can cut through a hide that no other animal on the Serengeti can get through. So we can slice it and we can get to the meat and we can use basically cleaver shaped rocks to break the biggest bones that we can actually smash into a full size elephant bone and get the marrow out of there. So these are new resources combined with new costs tremendously dependent offspring requiring sharing, requiring people to work together.

Eric 18:45

This is like a precursor to the farming trap. Like we we get these new resources, but they create a new, new dependency.

Dr. Josh Stout 18:53

Yeah, exactly. And so this this is something that happens over and over again. As soon as you maximize something, you reach the limitations of that thing. And so we maximize our brains and we've reached the limitations of what big brains can do. We can't make our brains any bigger and still give birth. It's just impossible. And so we've we've reached this kind of maximum situation. And what we do is the development happens outside the womb. And much of the development has now become the development of culture, not a physiological development. We have knowledge that gets passed down from generation to generation that makes us who we are outside of our physiology. It's not programmed in the way it would be programmed in. A mouse doesn't have to be taught to do anything. It just knows what to do. Whereas a baby needs to be told everything. Single thing.

Eric 19:43

Every single thing.

Dr. Josh Stout 19:45

Every single thing. And so this has been programmed into us as humans for the last 2 million years since we got big brains taking care of our kids has been essentially a number one priority as individuals and as communities. If a community doesn't care, come together to have kids, it won't have kids because it's necessary. If you're a man and a woman raising a baby, I'm sorry, these are gendered binaries, but this is biology. I tend to talk this way if you're a man and a woman having a baby and you have to take care of that baby, you're not going to get the calories needed to bring up the baby, let alone, you know, keep yourself alive. So you need to be part of a of a larger group. And everyone needs this. There there are there are periods of time where we all need to work together to actually produce infants. Otherwise, they just will starve. And a hunter gatherer female can produce enough calories to keep herself alive with maybe a tiny bit of surplus. But working with a mate, she can get enough to actually keep her toddlers alive and maybe have a get pregnant with another infant. And you know what? If her me doesn't doesn't actually find meat that day, other people in the group will be able to bring them meat. Now, I do have a tendency to tell these narratives that could reinforce certain sexist stereotypes of the female string, staying at home with the babies and the male hunters going out and getting food. This is something that is seen in hunter gatherer societies, but they've only recently started looking at the literature and realizing that basically every time women are out getting food, they call it gathering. And in time men are getting food, they call it hunting. And it turns out that they're actually in many ways working in the same projects. So one of the best ways to hunt is you have a whole bunch of people driving animals towards a hunter waiting with a spear. That's also the younger males. And the females can be doing this driving where as a large male who's stronger might be able to drive that spear home. You know, these these are these are facts of biology. I'm not trying to tell a gendered story, but you would imagine that if you sort of take a slightly larger view, the idea of only men do hunting, I think is false, that women are participating in the hunting, women are participating in all of the calorie acquisition. There's a few things that simply being stronger as a man probably have some advantages. The part where you're running to that dead animal and then try to defend it and bring back the food that was probably mostly men. But you can certainly see cultures where women would participate in this sort of thing. And there's been many times when, for example, in the animal world, men become too muscle bound to do the running. So, for example, the female lions do all the hunting, the male lions don't do the hunting. Every once in a while there's a situation where female lions will chase a buffalo towards a male lion who's big and strong enough to bring that buffalo down. But it's the women who actually do predominantly the hunting. So we could we could look at these these stories from that point of view. We could see that the women are actually doing most of the calorie acquisition. And every once in a while men are coming back with a with a large supply of meat. So there's different ways you could look at that same story.

Eric 23:14

Well, that sounds familiar. Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 23:16

So there's different ways you can look at that same story. But we tend we have tended to look at it from a totally male point of view. And I think that's a fancy that. I think that's a mistake. Yeah. And this is something that we've only recently started looking again. Papers were coming out in 2017 talking about how we need to re-evaluate these these this analysis of hunter gatherers. All right. So anyway, we've got this idea of a community raising offspring and that a lot of what the community is doing is providing culture, which allows the community to keep going and and acquire more calories for its offspring. And so this is a necessary part of being human right from the very beginning of having a large brain. So sort of let's fast forward through our cultures. You get to a farming culture and suddenly it's really adventitious to have more children in a farming community. The more children you have working the fields, the more calories you're bringing in. And so if farming families tend to maximize the number of children and experience famines every time it doesn't rain or there's a flood, there's problems with it. And so what happens when we when we get farming communities, we shrink, our bodies get smaller, our brains get smaller. And so for the last 10,000 years or so, our brains were actually smaller than they were as hunter gatherers in the Paleolithic. And our and our bodies shrink. So we, we, we became smaller, our brains became smaller and we started having more, more children. And so this is where we've been for sort of the last 10,000 years. Children were certainly not expendable, but it was a natural part of life, living in large communities that you would write off a couple diseases. And so very often you lose children before the age of five to these communicable diseases that existed because of farming. If you lived in a hunter gatherer society, you didn't have plagues running through your your city because you didn't have a city. Whereas if you're all sort of the huddled masses all living together in a city and you're doing your farming, you want as many babies as you can to to raise your crops and harvest your crops, and you're going to lose some to diseases rolling through. And so this is just sort of the way we've been living for the last 10,000 years or so. This didn't change much in the Industrial Revolution. People often think of the beginning of the Industrial Revolution as a a essentially a a rise of these these farmers moving to the city. And suddenly the city is becoming technological and the farmers are sort of swelling the populations of the city. But it turns out that a much of the Industrial Revolution, for example, London, was a population sink, that people would move from the countryside, move to London, and if you were poor in London in the 18th century, you were going to die of disease pretty early, and that a large portion of the actual offspring being born were offspring of the upper classes. One way or another. They were they were having babies with their maids or with prostitute, which.

Eric 26:30

You're saying the lower classes were just dying.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:32

They were not a population. They were not they were not a growing population For for the most part, the population was growing outside of the cities as we were getting better AI farming practices, we had mills that could drain the flower better. We had more transportation as as people were getting better food outside the cities and still having large, large population, large numbers of babies. The population would rise outside the city. They'd move to the city to to make money, and then they would die of cholera. And so, yeah, so so this was this is what we built for ourselves in the Industrial Revolution. And as this ended, as we were transitioning to a sort of post-industrial world, we figured out medicine, we figured out flush toilets and sanitation, and we started turning our cities into places where populations were actually growing as opposed to population sinks. And so it became reasonable to expect your babies to not die in the first couple of years. And as this is happening, we start discovering that to do well in the world, it helps for your children to perhaps get a higher education. And so we start competing for instead of how many babies can I turn out to make myself more food on my farm, we start competing for whose babies can can succeed the best in this sort of post-industrial society where everything is divided, decided by who got to the best university. If got to the best high school, who got to best junior high school, etc..

Eric 28:07

So now it's about technology. Even even if that technology is reading and writing.

Dr. Josh Stout 28:12

Even if that technology is reading and writing, it's already built into our into our into our species. Right. And we know we need culture to support our babies. We know we need passing knowledge on to the next generation. This has been done right from the very beginning, but suddenly, instead of just the number of hands you have working the fields, it's all about culture and it's all about who has the most knowledge. And it's all about who can win the game based on who has the most resources put into their offspring to develop the most culture, essentially. And so we start to transition to a world where we are having fewer babies because they're no longer on the farm. Those babies are surviving because we've defeated cholera by having flush toilets, and we now are seeing the families that have fewer babies doing better than the families that have too many babies. Babies have now become a cost, a resource cost. And we start thinking as rational beings about maybe I don't want to have as many babies because I need to put more resources into them if they're going to end up going to college. And so you end up with a situation where rationally people are needing more and more resources for their effort to to to rate to raise a child. At the same time as this is happening, we get birth control and we end up deciding that women can also have jobs as well as men. So now you need two parents working together, much like the hunter gatherers did to produce enough resources. I won't say calories at this point. Calories. We have an abundance, but it's a different kind of resources. It's money, but it's also knowledge, resources. And you need both parents working together to produce this. Single parents have a harder time. It's not impossible, but it's harder. And it becomes, you know, very, very difficult for a child without parents to succeed in any way. So you're going to be producing fewer offspring that you put more resources into and resources into, and you work together as as.

Eric 30:25

As two parents in the also.

Dr. Josh Stout 30:27

Sorry, putting more and more resources into into fewer children. And so this is a rational a rational strategy that we've developed where we realize that we live in an expensive world, where we're competing for a limited number of resources and that we're essentially at carrying capacity. There is no no one is building more and more and more universities that all need lots and lots of people in them. These are limited slots and if you get into a better university, you have a better chance of succeeding later in life than if you get into a place that isn't a university or you go into a place where you're not not as successful. Now, I'm mostly talking about sort of one path to success. There's obviously other ways to succeed in the world, but all of these require a lot of resources, a lot of culture and a lot of support from parents. So we are purposely limiting the number of children we're having because that way we can pay for their tuitions or their training or the schooling they're going to.

Eric 31:28

Need, where we hope we will have enough resources to do what is necessary.

Dr. Josh Stout 31:32

To do what is necessary. And if you have, say, six children, this is much, much more difficult than if you have one or two. And so across the world, we are seeing essentially a demographic collapse. Back in the 1970s, we were talking about the population bomb. We were going to explode in a sort of neo malthusian collapse of the world as we burn through all our resources, poison to the environment around us. This was happening. We really were going through that in your Malthusian growth, it was a logarithmic curve. It was going up almost straight up until about a decade or two ago, and now it's leveled off and it's leveled off because we are having fewer children really across the world. And it's starting to approach a point where we're about to enter a demographic collapse. So you need two children to replace the two parents. So if you have two parents, two children equals the two parents. Generally, you want about 2.1, 2.2 children, because sometimes someone dies in the process. So on an average as a culture, you need about 2.1, 2.2 to replace the parents. We're now at a point where many, many countries are well below two.

Eric 32:47

In Japan, famously.

Dr. Josh Stout 32:49

Korea just hit point eight.

Eric 32:51

Really? Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 32:52

So point eight. So think about that. That means less than half of the people in this generation are going to be in the next generation that.

Eric 33:00

Thanos is getting what he wants. Exactly.

Dr. Josh Stout 33:02

Yeah. So, so this could be great for the environment, but it's going to cause all sorts of problems for us economically. And it's a because, you know, a capitalism is built on, you know, constant growth. And so we in many ways, I think we're adjusting our economies so that it feels like we're still living in a time when there's not a slots for everyone where we're constantly adjusting to where we're at maximum capacity for growth at all times. So our universities only have a certain number of slots if, if they get more students, they'll hire a professor. But if there's not enough students, they'll fire professors. So there's always just not quite enough classes for the students to be in, which.

Eric 33:44

Is why there's always a line at the supermarket.

Dr. Josh Stout 33:47

It's why there's always a line of the supermarket, why there's always a lot, you know, they overbook the airplane tickets, everything. So everything about capitalism is designed to get you at that sort of maximum and a little bit beyond that.

Eric 34:01

So that 100 and 102%.

Dr. Josh Stout 34:03

Exactly. So everything is just a little bit stressed. But this means that we are constantly feeling like we have a few too many people. And so we're we're adjusting our population and down because of that in a rational manner. As individuals, we're having fewer babies, we're deciding we do we don't have a big enough house, we don't have enough income in how am I going to send these kids to school? All of these things we say, well, I'm going to stop at one or two, and that's enough because we don't have a lot of options. If we had more babies, the whole family would be poorer and not succeed and it would be very, very difficult. It's not impossible, but it would be much, much more difficult. And so these are rational choices we are making. And so I wanted to relate this to both saving the world and spoiling our children. That's what I sort of mentioning at the beginning. So what happens when you have fewer children? One, you put more resources into them. Now some of these are rational resources. See, I discovered when my first child was being going going up and trying to get into schools that she couldn't get into the the grammar school of her choice because she didn't have enough of a resume at the age of five. And so I realized that I needed to start putting these kids in programs, getting them documented their activities so that they could get into the high school they needed to get into so that they could then get into the right college. They needed to get into it. I needed to start scheduling their lives so they stop. We talk about where we overschedule our kids lives is necessary. If you don't do it, bad things will happen. You can't just let your kids go free range on the street because then I won't have documentation that they learned a skill.

Eric 35:54

It doesn't feel right.

Dr. Josh Stout 35:56

Yeah, and that's one side of it. So we're we're constantly over supervising and overscheduling our children. The next thing is we're worried about them now that we have fewer children and they're not dying at the age of five or before the age of five. We are constantly watching them and making sure we have covers on the outlets and making sure the babies are not falling in the well and this kind of things.

Eric 36:17

We're not having six.

Dr. Josh Stout 36:18

Kids because we're not having six kids. It's not that the people who had six kids didn't love their babies, but now when you only have one or two of them, it's absolutely rational to spend all of your time watching them to make sure they're okay.

Eric 36:30

And if you had six babies, did you have time to cover the outlets?

Dr. Josh Stout 36:33

Didn't have time for any of this stuff. Exactly. It wasn't that we didn't love our children in previous generations. It's just that we didn't have the time and resources to all of our time and resources to them.

Eric 36:44

Some of the previous generations might not have loved their kids, but.

Dr. Josh Stout 36:47

Well, it's certainly changed things a lot. Yes. You know, the the the the the what appears to us today as negligent. Only 30 years ago, for example, or 40 years ago was was completely normal.

Eric 37:03

Was normal.

Dr. Josh Stout 37:04

Right. And now and now older generations look at us and say, why are you spoiling your kids so much? And this is something that is is absolutely predicted by evolutionary theory that when you have fewer kids, you're going to be spending way more energy on them, spend more time looking at them, more time with them, and you're going to like it. We enjoy spending time with our children because evolution has programmed us to animals that didn't didn't produce children very well. And so any time you have extra resources, you're going to want to give it to your kids. Any time you have extra time, you're going to want to give it to your kids. People with one kid do know.

Eric 37:42

You're saying this is evolution narrowly driven, this.

Dr. Josh Stout 37:45

Is evolutionary driven. If you have one child, you're not going to give it. You're not going to have twice the time as if you had two children. You're going to have maybe a tiny bit extra time if you had two children, because you're going to take all that time, you're going to put it into your one kid because that is where all your evolutionary eggs are. That's your one basket. And so everything you're going to do is going to be you're going to do, you know, trying to mitigate risks. You're going to try and give them as much opportunities as you can. You're going to give them as many skills that they can put on a piece of paper for a resume.

Eric 38:15

In other words, you're not going to say go and play on the street.

Dr. Josh Stout 38:18

You're not going to say go and play it on the street, kid. And so the exact same things that we are now complaining about in our children are what our society drives us to do for rational, evolutionary reasons, because there really isn't another choice, but putting as much as you can into your children and and and slowing down the number of children you're having. So we're now entering into this this this demographic collapse, but we have avoided a malthusian disaster. So we have not poisoned our world. We have not used up all of our resources. And we're not going to now we're still having problems with global warming. This is a malthusian crisis.

Eric 39:02

Climate change, not having poisoned our.

Dr. Josh Stout 39:07

Climate change absolutely is. The population of the world is still going up. But the places where we are rapidly reducing our population growth are the places that produce the most carbon. And so we are actually transitioning faster than we expected to to a carbon neutral at least transportation world. The developing the developed world is is getting rid of our gas cars much faster than we thought we were going to. And we're actually really getting to some of our our carbon goals in terms of just burning fuels for transportation. Unfortunately, this is not happening in our factories quite as fast. Things like cement and aluminum are just tremendously energy expensive and there's not a lot of ways around that. And because the way capitalism is designed to have constant growth, we've actually programmed in constant growth, even when we have a flat to declining population. And so this this sort of cultural I resource I squandering, I guess is one way to think about it is going to be driving the the the increase in carbon use for some time. But overall as a planet we now have some breathing room because we've lowered our, our, our reproductive rate. And this is entirely based on education of women by having women in high school and in university, they are not having babies because when you're in a class, you're not having babies. I mean, some of my students are I've had students raise their hand and say, I'm pregnant right now, but it's very rare. Most of my students are nodding. Most of my students are female. This is something we can talk about at a later time, that men are not going to college the same way women are.

Eric 41:03

Okay, that's new and interesting to me.

Dr. Josh Stout 41:06

Later. Later thing on. Yeah, later thing. So yeah, most of my students are female, most of them are in their twenties or, you know, late teens, early twenties, and they are not having babies. And this is prime reproductive times. And so I am I am looking at whole cohorts of women who are not reproducing. And this is absolutely what is driving the the the the collapse in reproduction in in the developed world. And I think overall, this is a good thing. It will cause problems for us economically. And we need to start thinking about how we can have an economics not based on maximum production growing all the time with a constant, you know, winnowing of slots, longer lines, fewer seats on the airplane, all of these kinds of things. And so we need to figure that out. But that's a separate issue. These women are not having babies. It's going to save the world. And it's directly educating women. And so I ask my classes, think about your grandparents. How many how many babies did they have? Think about your parents. What when did they have their first babies and then think about you. How old are you now? When are you planning to have kids? And so in my parents generation, a lot of the people were having babies at you know, in the age of, you know, 20, 25 in that range, their parents might have been even younger. Not everyone, but and they would have had five or six kids.

Eric 42:33

You know, it's fascinating because you're talking about having these conversations with your students now in the United States. When I was in Korea, in the in the mid nineties, teaching high school students, they were already telling me that they were planning on going to school, they were going to go to college and not going to have children until later. And now 30 years later, you're telling me that they've dropped below one?

Dr. Josh Stout 42:58

Yes, they're less. Less than half of their population in the next generation.

Eric 43:01

Is this is.

Dr. Josh Stout 43:02

It's tremendous and it's and it's it's it's going to save the world. But we're also in for a big issue.

Eric 43:09

Economy is going to take a tremendous a.

Dr. Josh Stout 43:11

Tremendous hit.

Eric 43:11

Make what we need to make. We can't do right.

Dr. Josh Stout 43:14

So we need to have the people in, let's say, Africa who are actually at higher reproductive rates, come to our countries and help us produce things and be great. It would be great. I don't I don't see a lot of history in Europe or America of welcoming people from Africa. But Ghana right now has a reproductive rate of four, whereas, you know, Korea has 8.8. So you can see where the people in the world are going to be coming from. And we have not prepared for this in any way. Again, a separate issue. Yeah, but I wanted to point out that this this education of women is is is brand new. It has happened in the last generation. We can see it happening in real time. So people who are still alive have had grand kids where they have five or six grandkids and they're looking at their grandkids and their grandkids are having one or two at most. And so this is an intergenerational change that is happening in real time right now. The last hundred years have been tremendous. The last 50 years have been tremendous. So I've had two students talking about their grandmothers who had their mothers when they were 12. One was a indigenous woman in Colombia, another one was a Pashtun in Afghanistan. And their mothers had them when they were something like 18 or 19. And so here they are in graduate school at the age of 21, 22, no babies with a 50 year old grandmother saying, where's the babies? I want I want my great grandchildren. And they're they're they're so proud of themselves to be succeeding and to be in college. And they know they're not having babies early. And this is absolutely a conscious choice. And they're having a there's a generational split between between them and their and their grandmothers who don't understand why they don't have six babies already. And this this is something that is happening right now. And I think, you know, that's sort of an extreme version of it. But we see it in, say, you know, the conflicts with the baby boomers talking to us all about how we're raising our children wrong and we're spoiling them. And they they they they think we're we're doing a terrible job because we're spending all of our resources to to raise our children and to keep them safe. And they think that this is going to make us us weaker as a species, softer. But they don't understand is that we're looking at an evolutionary change that is happening really rapidly. And it's because of the way the world has changed. We're not on farms anymore. We're not working in factories even anymore. We are working in cubicles and to be a cubicle worker you need you're a knowledge worker. And that knowledge worker is based on a very limited number of paths for success, often through universities. And the best way to do really well is to have a lot of resources from an early age. So you can get into that grammar school, you need to get into this, you can get into the right high schools, you can get into the right college, so you can get a job that will give you the resources so that by the time you're, say, in your mid-thirties, you might have enough resources to have a child.

Eric 46:24

You are you are describing deeply based in class divisions that deeply.

Dr. Josh Stout 46:28

Baked in class divisions. And the the sort of the way out of these things is to have all of what I've been talking about, two parent households working towards a university success. And what do we see in in in areas of of say, the United States where family dynamics are collapsing is is we see a lot of issues. And so, you know, there's there is there is there is a lot of rural areas that are no longer farmers and they're no longer miners. And there is not a lot of other industries there for them. And they end up with us single parent families. They they have fewer options. It's a lot harder to go to university from a situation like that. And this has been understood for a long time as, oh, no, poor people reproduce too fast. So the Victorians were worried. They thought that all of these people moving into the city were going to make what they called the marching morons to, to to use a really un-PC phrase that poor people reproduce too fast and they were going to, you know, in our in our meritocracy, they were going to swamp the meritocracy with I too many idiots. So, you know, there's that there is the Idiocracy movie where only the poor people are having large families and smart people are having small families. But this is flatly not true. We have not had enough time to evolve AI actual intelligence differences between classes. We do not actually live in a meritocracy. A lot of the people who succeed, yeah, they're often smart, but what they've also had all of these resources given to them from an early age advantages. And so all of these things have have given them what they needed to have to succeed from birth. If you don't get that, it's a lot harder to succeed. It doesn't mean you're stupid. So this is no longer anything to do with genes, nothing to do with anything to do with heredity factors. This is just a societal one. So it's very much. Did you win the lottery at birth or did you lose the lottery at birth?

Eric 48:42

The other thing that that speaks to is that it could very well be fixed like this is.

Dr. Josh Stout 48:47

These are things that can be fixed. Absolutely. Absolutely. If we if we about another way to do our society. And it seems as though because we're in this transition period, we might be moving into a world where we could start to fix this. Well, we could start to look at ways to have resources spread a bit, a little bit more egalitarian through our society.

Eric 49:05

Start talking about.

Dr. Josh Stout 49:06

Politics. No, I don't want to talk about politics at all. But, you know, these these these things, as I was mentioning, that the tension and competition is built into the way we work as a capitalist system. Yes. I'm not saying that capitalism isn't a great way of producing resources. It has produced more resources than any other system out there, but it tends to not be really good at dividing those resources equally and so just like a silverback gorilla gets all of the mating opportunities, and unless you're the biggest gorilla, you get zero mating opportunities. We've worked ourselves into a sort of winner take all society, which is extremely stressful for all of us, and where we are forced to put extra resources into our offspring in the hope that they will become that silverback gorilla spoiling.

Eric 49:52

Our kids, save our earth, save the world. I see how educating women will save the world.

Dr. Josh Stout 49:56

Well, essentially, this is all part of the same thing, is that all of these resources that we're putting into our children is part of a process of having them reproduce later. We're keeping them in school longer. We're not having them have babies at the age of 15 or 16. They're they're they're they're waiting until their thirties, so they're twice as long 2 to 2 reproductive age.

Eric 50:17

So you're saying this isn't something that we should have a judgment on this is that this is an evolutionary change happening in front of our eyes.

Dr. Josh Stout 50:23

It's happening in front of our eyes. And we we keep arguing against it and say we shouldn't spoil our children. We need to figure out how to have maybe more babies because we're looking at a reproduction, at a demographic collapse. At the same time, how are we going to deal with a world with sort of limited resources and allocating these resources? And we really haven't as a society realized that these are all part of a single thing that's happening for essentially reproductive evolutionary reasons that are where we value our reproductive choices. We like not having more babies, we like not having more babies because it allows us to give more attention to our babies, which we enjoy, right? Evolution tends to reward things that give you evolutionary success. And so we we will automatically give all our time and energy and all of our let's keeping our baby safe energy into our very few babies that we now have.

Eric 51:17

So you're saying go ahead, spoil that child and enjoy it.

Dr. Josh Stout 51:21

A little bit of that. And also, you know, let yourself off the hook. This is this has been a sort of theme I've been trying to work on, is that a lot of things that are programmed into us, we then feel guilty about.

Eric 51:32

Yes.

Dr. Josh Stout 51:33

And I'm saying don't feel guilty about what you have no choices about. You know, if you are over over programming your your child's childhood and you're wondering, you know, because they're doing so much little league, are they having a real childhood? You don't have a lot of choice in that. They won't get into the right high school unless you do that. They will. If I don't sign up my daughter for fencing, that would have been a problem for her getting into a university. So she needs all of these things.

Yeah. So anyway, I this this is, I guess part of my my overall project to say a lot of what we're programmed for due to do we then feel guilty about and we need to start thinking about letting ourselves off the hook to a certain extent and not yelling at each other for, for doing things wrong. Just like I try and let previous generations off the hook to a certain extent for their negligence. This is this is how they were raised because it worked well. It worked well for them and it worked well for the last 10,000 years. And so we really are seeing a significant change in the way we live right now. It's not our imagination.

Eric 52:45

Fascinating.

Dr. Josh Stout 52:45

All right. So that's why I want to leave it.

Eric 52:47

Excellent. Well, thank you so much, Josh.

Links

Theme Music

Theme music by

sirobosi frawstakwa