Art and the Imagination

What is art? Today Dr. Josh Stout discusses cave art, and the development of art as a social and individual practice through the present moment where we see art uncoupled from time and medium.

Please scroll down for links below the transcript. This is lightly edited AI generated transcript and there may be errors.

Eric 0:08

Today is Friday, November 3rd. And here again with Josh. How are you doing?

Dr. Josh Stout 0:13

Josh I am doing well. I just wanted to start off with a couple of little things from previous episodes. There was an episode where I was talking about the relationship between our giant brains and how much energy they need from their mothers, and I vastly overexaggerated the amount of fat in human milk. I the way I tend to think about facts and figures is I remember them in relationships. And so I knew that human milk fat was twice that of cows, which is important. Right. And basically was the thing I was trying to talk about was how much how much energy we give to our babies. But I overestimated the cows and then overestimated humans. So anyway, I just I just wanted to correct that I human milk fat comes in around 6% or so. Six or 7%, not 18, as I said.

Eric 1:02

Very good. Thank you for correcting.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:04

And then the other thing was last last evening I did a show on Serpent and is Asian, and I just wanted to point out that was I did an experiment using my using my phone, sitting there with a cat on my lap. And I definitely went far afield from my normal areas of expertise. So if any of the chemistry turns out to be wrong, I will try and check it out and get corrections LED later. Time and follow up on that and I'll probably be coming back to Serpent Analyzation at some point. There's there's vastly more to the topic.

Eric 1:35

And I and I do hope that that as you have more ideas that you you need to get off your chest when you're not with me that you will continue to do recordings on your own because we'll will put those up that.

Dr. Josh Stout 1:47

That that is the goal. And just just for those who don't know what I'm talking about, Serpent ionization makes hydrogen that comes directly out of the ground and we can run our entire economy on it perfectly cleanly and produce zero pollution.

Eric 1:58

Are we not doing that? I guess because we've.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:00

Just found it and that's what we that would be the next kind of thing we talk about moving on to today. All right. Moving on to today's discussion discussion. There's been a couple of articles recently in The New York Times on art and on sort of our relationship in the modern world to art. And I found them interesting. And so I wanted to do a basically an art history talk, but from the point of view of human evolution. So starting with the beginning of human art and then just bringing us right through to what we're talking about today, I.

Eric 2:31

Can't wait to hear how you define the beginning of human art.

Dr. Josh Stout 2:35

Well, that's super easy. It's sort of a hashtag it. So yeah, so what I was what I was reading about was that the art we have in the modern world has become outside of time. It's a temporal that we no longer have a firm standing in any particular era, and that this has happened really across the board. I can see it in my own music. So I, I look at the music I listen to and it's from the 1930s up until yesterday, and it's this whole range. And what is that range? That's modernity, right? So between the wars, right after World War One, basically visual arts, all change and music starts to change. And this is when the birth of modernity, we no longer have the classical image of the guy on a horse with a sword, right? That that, that that goes away. We lose classical music, we lose classical poetry. And then these were replaced by new forms. And these new forms are changing all the time. And so we go through these upheavals over and over again as, as, as visual arts change, as music changes. And it happens more and more rapidly. And then in the last real literally decade, we've gone outside of time itself. We are now in a region where everything is a giant jumble and happening at the same time. And so the thesis that was in the Times was that this means that our art itself has become confused and will not leave anything for future generations that will make any sense because it's from all different times and that we as a time may not be remembered because of this, because we are now essentially a historical left.

Eric 4:16

We have no way to define ourselves.

Dr. Josh Stout 4:18

We are not a time. Okay, So in some ways I agree with this, but I think that is actually a definition. This is this is a moment unlike others. And so therefore, this is a moment and this kind of contradiction is is it's constant in the art world. As soon as you destroy something, you've basically created the thing that you just destroyed. Right. And it is.

Eric 4:42

Destruction itself is a thing.

Dr. Josh Stout 4:44

Is a thing and becomes, you know, the next the next thing, the next thing. So yeah, so so the thing we're in right now is this this, this a temporal moment. And so I wanted to think about what time is in relation to art and, you know, go back to the beginning of art time. And then for art again and see sort of how we got to.

Eric 5:04

Some of this was, was this the thesis of the article that you were reading, that our art right now is outside of time? Yes. Not definable and won't be remembered. Yes.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:11

Yes, exactly. Yeah, that was the thesis and I agreed with it. I think it's true. And then I think the opposite of it. Because it's true. This is our time. This is the moment. Right? And so this this is this is the sort of the nature of defining things within art is as soon as you define something, you've moved to another step. Essentially. And so that step we're in right now is a moment. So we're outside of time, but happening within time are time is a temporal.

Eric 5:41

To actually be outside of time.

Dr. Josh Stout 5:43

But yes, right. You know, so you can access things from any time at any moment, anywhere. Right. This is the nature of the modern information world. So going back to the beginning, we've just become humans. Our brain is expanding. Are the regions of our brains that govern both tools and language have expanded. So the left hemisphere is much larger than the right. We become right handed. We become skilled with tools, we're making new tools, and we see this explosion in in New technologies, which I've already talked about, things like fishhooks and needles that require imagination. At this moment we find in South Africa an 80,000 year old cave with, as I said, a hash tag. Someone made a sort of scratch in a piece of ochre. They were probably using it to make body paint and they happened to make a pattern out of it While they did it right. So they didn't just scratch it, they did it in both directions.

Eric 6:39

So it wasn't just random.

Dr. Josh Stout 6:40

It wasn't just random. Now, we clearly had an aesthetic sense even before that. As soon as I'm sorry.

Eric 6:47

I have a question, which is that you don't think that pattern was you don't think that that pattern was actually the purpose of the art, The it was a byproduct and that they were trying to get a pigment for body paint.

Dr. Josh Stout 7:00

Probably because what, what what is found next to this piece of ochre, which is a stone and that you can scratch the stone to get pigment from it. What it found next to it is a abalone shell with, with pigment in it. Right. So someone was collecting this pigment and then putting it basically in a palette. There's no paint on the walls. So the idea is that what were they painting? They were probably painting themselves very interesting. And it's fun to do. I mean, I did this as as a child. I would go down to the beach, I would take red stone, scratch the ochre off of it, and paint myself with it. All the kids did. Yeah. Because if you live near those rocks, that's what you do. But I didn't tend to make patterns with it. And if I had made a pattern while I was doing it, that would have been art. It's not high art. It could have been, you know, very beginning kind of thing, but it's something that would leave a mark, right? You scratch into a rock. It's there for a really long time. In this case, 80,000 years just sitting there. No one touches it. There it is. You pick it up 80,000 years later. So this is what I wanted to get at is sort of the sense of deep time in the beginning of art. Even before that, when we were making hand axes, there would have been some sort of art concept involved. So if art is anything, it's a modification of some sort of substance or the modification or, you know, production of say, a song or sounds right, it's doing something that wasn't there before and then with some sort of way of conveying information to someone else so that before this hashtag, that hashtag would just say, look, here I am doing this thing right. It's a pattern. And so we generally think of this as associated with these advanced technologies. fishHooks, probably the development of language. Before this, what we had was hand axes. And with four hand axe, this is this is a stone tool about the size of a cell phone for the same reason you hold them in your hand. And we probably would have been able to do a hand axe without too much advanced language. You can just sit next to someone and learn how to make something like that. So communication could have happened direct sort of body to body communication, just following the patterns and when the hand axes were made, they had a certain aesthetic value to them. They might have stripes in them. Sometimes there would be a fossil that was put directly in the centre of the hand axe so that you could see it. So it wasn't that we were outside of aesthetics, but we were not making these things for an aesthetic aesthetic reason. So they're not considered art and they don't have the same kind of meaning that a symbol or a pattern put on a wall or put on a stone purposely does, right? So that piece of ochre was not a tool. It was not for anything else, it was just scratched. Now it might have been used to make the pigment, but when they did it, they were making a pattern. And so that's sort of the very, very beginning. And coupled with this with the abalone shell, with the pigment in it gives the idea that we were painting ourselves, we were doing something with this pigment. So it's not just a hashtag.

Eric 9:56

We weren't just scratching away, we were collecting.

Dr. Josh Stout 9:59

Yeah. So the whole the whole.

Eric 10:01

Sort of thing was part of a multistep process.

Dr. Josh Stout 10:03

And are pieces of evidence showing that this was art. And so this was a real transition from we might have been able to appreciate pretty things before this, but now we're making things that have a meaning, that have some way of conveying something. Now, it might just be I have red on my face. So, you know, this is a special moment, right? I made red on my face. I look cool now, right? There could be all sorts of reasons you might want to paint yourself. It could be rituals, or it could just be, you know, the early makeup, right? I have my, my, my, my, my children played around with this. If they wanted to put rouge on their cheeks, they would actually scratch some ochre and put some rouge on their cheeks. You know, these these these these are things humans have done for a long time. And they have to do with, you know, our relationship to each other and putting marks on ourselves. But again, it has to do with with both a combination of beauty and and communication.

Eric 10:59

And maybe a little bit of controlling our world.

Dr. Josh Stout 11:02

Controlling the world. Yes. So that's that's that's sort of the thing that comes later. As soon as you have a symbology, you can you can record your world. You can control your world.

Eric 11:11

The act of marking yourself.

Dr. Josh Stout 11:13

Absolutely.

Eric 11:14

Yeah. In a way that never was possible before.

Dr. Josh Stout 11:16

Yeah. So the first thing we start to see on cave walls is handprints. So we take we take that mark on ourself and then we put it onto the cave wall. And so this is, this is our signature, essentially. And so I ask my students, you as a human, why would you put your handprint somewhere? And I show them pictures of of modern graffiti, of handprints on things. And they're saying, well, just essentially I was here, I think, yeah, yeah, I agree with that. But sometimes there's weird ones, right? You might be part of a of a cult or a group. So people would make the equivalent of gang symbols, you know, different weird finger combinations and put those on a wall. And so that's a particular signature. There's one place in North Africa where they have human handprints, and then the handprint of a very large lizard put directly over the human handprint. You can't say why, but that was a group that had a particular thing going on.

Eric 12:04

Didn't say why, but it certainly says something.

Dr. Josh Stout 12:06

Says something. Yes, there's something. I am the Lizard King. Yeah, yeah. No.

Eric 12:11

I had this lizard in my hand.

Dr. Josh Stout 12:13

Yeah, a very big lizard. And they're not all the same lizard. And a lot of people are doing this at different times. So they were the lizard people, right? So there is this this becomes, you know, one of the first aspects of art is marking that you were here when we start to see what we call a true cave art, parietal art, the art that is painted on a wall, So once once that begins and we start to actually paint animals and things like that, we've we've, we've, we've truly entered the world of abstraction. And until relatively recently we had understood this is happening in Europe. It was probably for some perhaps slightly ever so slightly racist reasons. Any time you look back in our anthropology and archaeology, as soon as you get back into the fifties and forties, the stuff you see is unbelievably racist. Even if they have a reasonable theory on something, they'll just throw in a couple of racist words just for fun and you're like, Why did you even do that? Right? So, you know, for example, someone found hand axes all the way to India and then none in China. And so they could have just said that, but they're like, well, maybe the people in China weren't smart enough. Just just throw that out there. And they're not even talking about humans. Right. We're talking about, you know, Homo erectus in different regions and and and they just just throw it out there for a, you know, basically racist reasons. So we're finding all this art in Europe. We also find art in other parts of the world, but we assume it's not as old because it's not in Europe and was a somewhat of a of a sort of. Yeah, exactly. And so there was this this this, this self-fulfilling prophecy. Now, it wasn't entirely for racist reasons. If you think about the European art, what you see on the walls, you see woolly mammoths, you see woolly rhinos, you see things that don't exist anymore. So, you know, they must have been real. So as soon as we saw it, we didn't have to be, you know, experts in dating, you see a mammoth painted on the wall say, you know, it's 1850 or something, and you're like, oh, that's old. We don't have those anymore. That's incredible. That's like an elephant with fur on it. And so we knew that these were incredibly old. When you go see the ones that were done in Indonesia and Malaysia that are actually potentially older, but we've only recently realized this. They're the same animals that are there today, so you can't just look at them and realize they're old. So it wasn't entirely racism. It's not always racism, but there's always just a sprinkling of it, particularly in the earlier stuff, and that we hadn't been really thinking about it that way. We just made these assumptions. It wasn't in Europe must not be old. So what happened was they started, they started peeling off layers of the calcium carbonate that comes from the caves. They were able to separate those layers and find the bottom layer. So microscopic stuff and then get the uranium byproducts out of that bottom layer. That would give you an accurate date. And they discovered that these things in Sulawesi, in Malaysia were 40,000 years old or older.

Eric 15:06

You're talking about the bottom layer of pigment on the stone.

Dr. Josh Stout 15:09

No, the the bottom layer of stone all over the pigment. So as a cave is forming, the water is dripping down and evaporating. Lee Leaving calcium carbonate. Now, if there was a lot of it, you wouldn't see the painting anymore. It would be covered. So we're talking very microscopic, transparent layers. When you put those under a microscope, you can see individual layers of this stuff like, like, like paint layers, like, you know, someone would paint it and then they paint again. The people pry these things apart. You then have minuscule, minuscule samples, but you're looking for radioactive isotopes again. So less than one part per million of this tiny thing you just did is going to be the isotope you're looking at. You're measuring picograms 15 grams.

Eric 15:53

And then once you find that you've, you know, dated it.

Dr. Josh Stout 15:56

You absolutely dated. It must be older than this thing, right? Because the layers of stone were over it. And it's very easy to get younger dates, but you can't get older dates because it was under a layer of stone. So you're all your errors are going to be towards the younger end. And so it's a really like firm way to say it must be older than a particular date. And so these dates are 40,000 years, 45,000 years, predating some of the European art. Really most of the European art. So it turns out but we've only known this about 28, 2010. So this is this is brand new stuff that we've been finding out and it's changing our concept. So any any any racist idea that art began in Europe is totally false. While we were leaving Africa, we were painting everything. We also we also don't find a lot of we were.

Eric 16:45

Killing and painting everywhere we went.

Dr. Josh Stout 16:47

Exactly. And so we don't find a lot of this stuff in Africa, mostly because there weren't caves of the right type. Now, it may turn out that some of these African paintings that we thought were young for the same reasons, right, we just assumed may well be very old and there may be going back much further in time. The ones that we found from 80,000 years ago in South Africa are almost the only evidence of very early cave art in Africa. I bet you could find things from 80,000 years and 70 and 60 and 50 because then we have it at 40 in Indonesia, right? And so it's out there somewhere. We just haven't found it yet. And so we have to just sort of leave behind the idea that Europe is where art happened, right? It's just that there were a lot of really great caves in the limestone of of of of where sort of Spain France and Italy all come together.

Eric 17:38

People to be in but for art to be preserved.

Dr. Josh Stout 17:41

For art to be preserved. Right. If you're if you're just on the if you're painting on a wall even with a little ledge over it, that's not going to survive. It's got to be down. It's got to be in deep within the caves. And it's and it's got to be in some way protected from bats. Apparently, bats getting into a cave tends to degrade it. Now, a lot of the early theories are, why did we only paint really deep in the caves? I'm beginning to think that we painted everywhere and only the stuff really deep in the caves survived. And so there was a lot of talk about these ritual spaces. I agree they were ritual spaces. They were really hard to get deep in the caves to paint these things. And how did you get to paint on the ceiling and all these kinds of things? All of these things took a lot of work. You had to do it by torchlight. They were very, very deep in caves, interesting ritual spaces that I will definitely be talking about. But I think the stuff in the front of the caves was there, too, and the bats got there and just destroyed it. So I think there's sampling bias and a lot of what we do, you know, it can only occur in certain kinds of caves.

Eric 18:36

If you've ever been to Pompeii, you see that every wall that exists, every surface was colored, everything.

Dr. Josh Stout 18:42

Right? Right. So this is this is this is an instinct. It gives us joy to make art. Right. And that is that is something that I have accentuated in or I've tried to have the theme when I talk about things, things that evolution likes to select for, give us joy, right? Running around and throwing stuff gives us joy. Painting gives us joy. Talking to people gives us joy, right? These are things that that is selected for. Obviously, you know, a relationship with a member of the opposite sex you're attracted to gives us joy because evolution really likes to select for that. But these are all things that are that are, that are naturally occurring, things that give us joy. Now, not everything that gives us joy is good for us, right? Evolution wants us to eat lots of sugar and fat also brings us joy, right? Literally, our dopamine and serotonin levels go up when we eat sugar and fat. Not necessarily good for us. Luckily, art is somewhat good for us because we'd be doing it anyway, right? You tell the kids in your class not to draw on the desk and they're all scraping with their knives every time the teacher's back is, you know, put their initials on saying, I'm sorry, I'm thinking high school, you know, like carve it on the bottom of a desk. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. My, my. Seriously, my students, none of them have Nice. Yeah, I meant I mentioned games that involve throwing knives to my students, and none of them had ever heard of anything remotely like that. Yeah, Yeah, Some of it's a different era, You know, I was. I was. I was taught by people who had, like, grown up in the forties and fifties that throwing knives was a perfectly normal game. It was.

Eric 20:13

A thing called lawn darts.

Dr. Josh Stout 20:14

Darts and mumbly Peg. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Anyway, these things are passed. We live in a different era now, but, you know, throwing stuff is still fun. Yeah. Anyway, back to art. So what we understand as the history of art is basically defined by European periods, but that's only because we've only recently started to understand that it's not the rest of the world. That means that art is in the rest of the world and that there are overlaps between these regions and periods and productions. But I'm going to give you the sort of general, let's say, year 2000 version of how we would have understood art, art to be produced. You know, I think things are changing because of these new dating systems. We know it was everywhere, but the earliest kinds of art you see in Europe are from about 40,000 years ago, and they are what are known as the Venus figures. There's some discussions whether you should call them that, but there are certainly these AI apparently ritualistic figures. They tend to be voluptuous, voluptuous women, often without heads or with that or with their head features, somewhat de-emphasized large hips, large breasts looking like some sort of fertility symbol. We get our ideas of what a fertility symbol is from some of these images.

Eric 21:33

These particular images are from about 40,000 years ago.

Dr. Josh Stout 21:36

The very earliest ones. Yeah. Yeah, 40,000, 30,000, very, very early periods. And basically it was thought that this was predating art on the walls. And so that three dimensional art was seen as a slightly easier way to approach the world than to dimension art, because it was less abstract that you could carve something and it didn't take as much brainpower as putting something in two dimensions. I don't know if this is true or.

Eric 22:05

Not having a hard time agreeing with that, but.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:08

Fair enough that that was a zero. There were a lot of weird theories about these things. So we find these these these figurines tending to be earlier than the paintings. And so we say this is this is the order things happened. It might just be that these figurines were really convenient to make. You could carry them around.

Eric 22:24

And they're made of stone.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:26

And they're made of stone or.

Eric 22:28

So they last.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:29

Or, you know, ivory or antler or some of these other things that if you put them in a cave, the last of these ideas were then sort of revamped when we found some cave art that was contemporaneous to the carvings. And it turned out that people were indeed.

Eric 22:44

Frequently.

Dr. Josh Stout 22:44

Older. Yeah, well, no, not the ones, not the ones in Indonesia, but in Europe. We found cave paintings that were the same age of these. So again, this whole theory went down. There was all sorts of theories. Some people thought it was all about male and female images and putting them together for for mystical reasons. There was people thinking that they were practice. You know, that certainly that is something that you can do with your imagination if you're a an athlete and you think about putting a ball in a basket before you try, you will do better. And so this is something that athletes have learned how to do. They can they can they can use their imagination to practice going through something. And they have measurable improvement because.

Eric 23:25

Visualizing the activity absolutely stimulates the areas of the brain that you need to actually do that thing.

Dr. Josh Stout 23:31

So the ritual aspects of these things may well have been coupled with actual improvements in hunting skills, right? So one of the questions I asked my students is what evolutionary purpose does art serve? Right? So in addition to communication, it might actually give you some sort of advantage to be able to picture an animal that you're then going to hunt. You might be communicating it to other generations. This is the thing we hunt, but you might also be practicing stabbing at it. And sometimes you actually find stab marks on the on these animals and you'll see place where someone stabbed it with a spear.

Eric 24:07

Practice.

Dr. Josh Stout 24:09

Other times, there is no way they could have maneuvered a spear into that position, but they're still stabbed. So it might be a ritual killing, right? So someone might have might have taken a stone and jabbed it from close by, not the way they would actually be hunting, but just to show that this thing had in some way been killed. The animals are often shown fat, sometimes they're shown pregnant. These are things that are producing meat for the group. And so that, you know, that might be simply the reason they're important. It's really interesting to think about their connection with shamanic practices. Now, obviously, we're talking about something 30,000 years ago and comparing it to something where we talked to 19th century shamans and we have an idea of what they were up to or even modern shamans. We have some idea of what a shamanic journey might be. Some of the best information we have is in Native American peoples, like the Mayans actually have living shamans that can help explain the hieroglyphics from six 700 years ago. But even that is barely touching 30,000 years. Even if you go back and you read the Egyptian stuff from 5000 years ago, that's barely a clue what might have been happening. So everything that we're talking about is going to be speculation when it comes to reasons. But we can see that connected to how we have made art for a very long time is ideas of our own spiritual transformations, our own spiritual journeys. You know, Egyptian art has lots of animal human hybrids where we're taking on energies of certain animals and trying to use them for our own purposes. And so this is likely to be something that was happening in these caves. I can't say it for sure, but you see similar activities. There's a there's a famous there's a famous painting on the cave wall called the the Hunting accident. And they thought that a a bull had run down a hunter and the hunter had stabbed the bull. And you can see what looks like loops of intestine coming out from underneath the bull where the bull has been stabbed and the hunter is lying on his back. And it's called the hunting accident.

Eric 26:17

There is this work of art.

Dr. Josh Stout 26:19

There's this this is this is this is European. It's exact Lascaux. So it's, you know, I don't know, 16,000 years old, something like that. Okay. In France and I it's it's the early versions of it, you know, where we're emphasizing you look, it's a bull. The guy lying on his back is basically a stick figure. Stick figure. And he's been run over. And it's just sort of a thing that might have happened. But if you compare it to, say, Shaun, that's a hunter gatherer group in in Africa, they do modern rock carvings and they'll often show a bunch of animals with a shaman lying on their back and they can say this is a shaman lying on his back. So this is direct with the animals that he's dreaming. And so the shaman dreams the fertility of the animals and this may be what we're seeing in this art. So this this guy lying on his back.

Eric 27:13

So it's not a hunting scene at all.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:15

It's not a hunting scene at all.

Eric 27:16

He may not be his dream thing.

Dr. Josh Stout 27:19

The animals that will be hunted and this is being painted on the on on the wall. And it's a vision. And so one of the hints that he's not just been run over is he has an erection and so on a stick figure. You know, it's not a lot of details, but you can definitely see that he's not just lying there imagining this thing. And so one of one of the ideas that may be happening is either through chanting or drumming or some other I rhythmic trance induced state or even use of some sort of hallucinogen. Many of these images have relationships to these these hallucinatory trances. So the Sean art showing the shaman lying down, he's got one knee up, so you can't tell. But he he may well also have an erection. And this is something that's common with a number of hallucinogens in the trance state is is is also sexual. So for example, if you look at Latino art from the Caribbean, they'll often be a shamanic figure who has taken some sort of hallucinogen. And you see him with his head back as as the muscles in his neck are tightening up from from from that state of being. He's got the smile, the rectus as he's brining his teeth and he's got a big erection. And so this is a classic look of of of the shaman in a in a in a trance. And what these animals may white may well be is objects of this trance. And so you see many of them are just dots. And so one of the ideas of, say, a shaman in in Siberia might see is they might see dots swirling in their mind and that these dots then coalesce into animals. And so often on the cave walls, you'll see lots of dots. Sometimes you'll see animals made of dots, and then you'll see an animal made of dots with an outline around.

Eric 29:14

It is the idea that the shaman is is trying to call into being a good hunt is that.

Dr. Josh Stout 29:22

Was something like that, but also communicating with it. Right. So this is this is this is the dream time. This is the world of of the ancestors. This is the world of the animals. So this is you, right?

Eric 29:33

These so even in the time that these works of art were being made, they were depicting something ancient from their mythology, perhaps.

Dr. Josh Stout 29:42

Again, I am in full speculation mode. Yeah. Okay. So, you know, I'm trying to say that this is what shamans do, right? They visit the world where the animals live. They bring the animals to be hunted, but there is also relatives of theirs that they're talking to. These are ancestors, These are relatives, These are these are these are beings that they're in communication with and that this is done through the trance. So they're you know, sometimes it's members of the tribe have a totem that they're becoming that animal. Other times it's, you know, the animals that they hunters as a group. But this is a common thing where also the animals go into the shaman. And so this might be also depicted in some of the art, just like in the Egyptian art, they take the powers of the animals into themselves. Very often in cave paintings you'll see a human with an animal head. And so sometimes these are called sorcerers. And then other people say, Well, we have no idea. I agree, we have no idea. But one reason why you might want to put an animal on a person's head is they've taken that animal into themselves. And so, again, in this sort of shamanic trance version of it, again, very speculative. You could imagine these things as taking the powers of the animals and then becoming one with them as as part of their power. So inside of a in this this very early cave from, you know, or Ignatian period, maybe gravity and you see groups of lions on the wall. And then this is particularly interesting because these are groups of what looked to be female lionesses. Who are the hunters of the lions. Right. So these are the hunters. This is female power painted on the walls of these caves. Now, people have pointed out you can't tell the cave lions might not have had manes. You can't tell if they're females. But I will tell you, you do not get large groups of male lions together. You only get groups of female lions. You know, in a in a pride, the males will just fight. So there might have been one or two males. You can't tell in that picture. But when you see a group of lions painted on a cave wall, you are looking at female power. Okay? And as part of this evidence, right in the center of that same room, in this very, very back area where the where the ritual is happening, you have a Venus figure made out of a stalactite. So she looks like a an actual carved Venus figure. Except she's not just a carved Venus figure. One leg is a bull, a minotaur, a bull's head on a man's body. The other leg goes up into a lion. So if you have a lioness, the female power combined with the male power as the bull and they look like they're having sex, basically the female is slightly bent over and the male is behind her and they look like a sex act happening between a minotaur and a lioness person. And if you get at the right angle, you can see it also looks like a yin and yang. The male is dark because of the paintings of the bull, and the lions are sort of a lighter tawny color. And so you get this kind of combination of the light and the dark, and then the whole thing is forming this goddess. And so it's very difficult to interpret something like that outside of a ritualistic kind of images of this. Yes. Yes, there are. I Verner Herzog did a lovely piece on this called Was It a Cave of Dreams? I have.

Eric 33:06

To find.

Dr. Josh Stout 33:07

Yeah. You want to see that? You want to see that movie? Yeah, because there's not a lot of people are allowed back there.

Eric 33:11

Cave of Dreams.

Dr. Josh Stout 33:12

Cave of Dreams. Yeah. Yeah. Not a lot of people are allowed back there, but it's a it's an amazing, amazing site. I have not been back there, obviously. I've just seen the pictures. All right. So anyway, but these are these are these are clearly ritualistic things. And you can see this development happening within European art. It's probably happening other places as well. And you see it become more and more ritualized as time goes on, as you go from the orientation to the solution to the Magdalena and you get to later portions of of cave art and you see more and more of these rituals, you get ritualized burials. You you start to see more characteristics of the animals. You see more life in the animals. So the animals start to have expressions and feelings. And there's this general idea of development. We probably had it at other places, at other times for a long time. So this this idea of development is definitely imposed on what we're seeing. But there's still a progression. You know, even if a lot of this is being imposed, the later stuff does tend be better. So culture is developing over time, even if it's a very long time. These there's roughly, you know, 10,000 years within each period. So these things are widespread. You see similar symbols in several caves over a very wide from Spain to France. So this is an identifiable culture with developments over time. And this leads directly into, you know, the Neolithic and moving out of the caves and putting these images on pottery. I personally love the Bronze Age because to me, these things look like sophisticated cave paintings put on to pots that I go see at the Met. Right. So they they're they're they're they're, they're well thought out but they're a kind of art that personally I can understand I can I can relate to these kind of symbology by the time you get to classical art, I have a harder time one I would have a more difficult time doing it. But it's been so formalized that you you lack the freedom that you see in these earlier periods. And so this is what I see modernity have going back. The modern artists talked a lot about primitive art. I don't like that as a term, but they were going back to these these these symbols that are older than what is seen in classical periods. So, you know, sculptures were going back to pre-Columbian Arts. They were going back to even before the the Mycenaean somewhat some of the the early the early idols like the the stargazers these are pre Bronze Age idols found in Greece. I carved one of those that's the one with the with the Opals in its eyes. So these are images way before the development of of of classical art and I think this is kind of what we're doing right now. We've, we started by going back to the very earliest art or earlier art with modernity. This is what Picasso was doing this this is this is what Brancusi was doing This this this is what the major sculptors of the day were going back to some of the the pre-Columbian work. And then we tried to go from there. And so art became faster and faster, always looking for something new. And now we've arrived at this point where we've lost, we've lost any connection to time, and we started to lose connections to things themselves. And so one of the one of the movements within sculpture right now is that we are. Postmedia So you have things, you know, in the sixties, you have, you know, Marshall McLuhan saying things like, you know, the medium is the message. We've now transcended that to the point where there is no medium, there's just message. And the message could be just put on in a projector and projected on the side of a building. You don't need to have actually anything made.

Eric 37:01

But that is a medium in and you can't not have medium that.

Dr. Josh Stout 37:05

I know. It's a it's a it's a crazy statement. And in some ways and this was why I wanted to.

Eric 37:11

I see where it's going. But how do you how do you have a message without a medium to carry the message, you can't convey the message.

Dr. Josh Stout 37:19

Okay. So this is why I wanted to get to Marina Abram. Can I say her name? ABRAMOVIC Yes. Abramovic The other article in The Times was by this woman. It was an interview with her where she was describing her art, and she is a conceptual artist who does performance art. And so this is art without a thing. This is art that is just a an activity. And she described as art as the highest form of communication, doesn't have an object anymore. And so.

Eric 37:53

You know, art doesn't have an object at.

Dr. Josh Stout 37:55

Its highest form. So just like those people with hand axes were able to make a hand act just looking at the person next to them without talking, we've returned to this earliest moment where her idea of the highest art is not saying anything at all, changing what is inside yourself. And then having an impact on the person you are looking at and changing them and that you've now lost all mediation. So it is like the disciple going to see the master and sitting next to the master meditating and learning directly from their body what energy is directly from their body, How this flows in them.

Eric 38:34

The art is the spirituality.

Dr. Josh Stout 38:36

The art has become the spirituality. And so she has is seeing this as as the highest point in art. And I do agree with her. And I think, again, this is at the moment when art is completely broken, right? It's become nothing at all.

Eric 38:48

You can't because you cannot transmit it except to one person at a time.

Dr. Josh Stout 38:52

Well, you could if if you're if this is a video. Right. Someone could see this happening. There's there's no reason why there can't be.

Eric 38:59

That transformation, though. Doesn't that require personal interaction with the artist in this case?

Dr. Josh Stout 39:05

Well, imagine a video of someone making a hand acts right? Someone else could make a hand act simply from that video. Right. So there is a.

Eric 39:12

Maybe.

Dr. Josh Stout 39:13

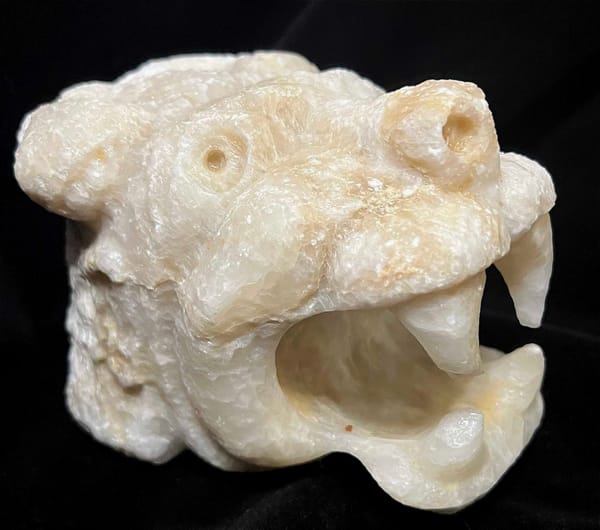

It is possible there. It is possible to record these things. But yes, these are outside of time. It could be a performance on a stage and the whole audience is watching what this thing is. So this this is communication prior to language. This is communication at its most essential. And I agree with her that that is the highest art being able to just put something out there. But I also think this is the end of art because there is nothing being made, right? There is no further thing. So this is what I was talking about, how things sort of destroy themselves and become the next step. We are now outside of time and we're outside of matter. We have left the ability to have a time. We've left the ability to even even even make things. And so we're at a moment in time where we are a moment and where artists are still making things, but they have sort of this new meaning. And I sort of wanted to talk about that. So in my own art, the art itself is about time and I'm making it in a medium that is purposely surviving. My wife, Wendy, is doing similar things with her cave art, so she is taking pigments, making them herself that she gathers from from from the cliffs and then paints that in this in the style of cave art, because these pigments will never, never fade. Right? They are. They are. They're iron oxides. They can't go anywhere. They they will not change over time. Same thing with my Jade. It really is stable. It's not chemically active in any way. It will just sit there for thousands and thousands and thousands of years. And so the art itself is about time. It's referring to earlier periods of time and it is about something that will last. So we've gotten back to a medium. It's not exactly the medium is the message. The message is being conveyed within the medium, but it can be conveyed to the future. And so I'm trying to understand the moment we are in time and and what has happened to art as a whole. And I think it has I think I think I think, you know, my is correct that we have transcended the matter of art entirely, which is why I think it's time to start making art out of stone again, you know.

Eric 41:33

And and so you are. Yeah.

Dr. Josh Stout 41:35

And so I am. And so this, this is something that, you know, we had left behind, up, up, up until really the Renaissance art was made out of stone. It was carvings, it was statues. It was right, right, right, right through that. Now, there was obviously art up on cave walls, but the but the statues that people made, those those Venus figures were always going to be the most precious possession you could actually carry. You can't carry around a cave wall. And so the idea of of arts as things that you would have had always been stone and it was only really when we get to paintings in the Renaissance where the them, the ditches and such can put their paintings up on the wall and paintings are being bought, that you get the commodification of painting itself.

Eric 42:16

You can't have.

Dr. Josh Stout 42:18

It and other people can't have it. You know, later we get we get the museums where the people now are allowed to see these things. Napoleon, you know, bring these things into, into being where, where, where a nation can show off its its loot, literally, that it has gathered from other places, not necessarily with its permission, and then put it into a museum for everyone to see as a display of strength. Right. So art starts to form these these these other kinds of of abilities, but it had always before that been a way of sending a message in time. So Pericles talks about the highest form of art isn't stone. It's it's the things we say to each other. It's the memories we pass on. But he was saying that everyone knew that Stone was the highest form of art. He was trying to show how we can transcend that, that, you know, if you want to be remembered, get yourself carved in a piece of stone. And that's what the Greeks did, right?

Eric 43:07

And the only way you get yourself carved on a piece of stone is if you tell a really good story.

Dr. Josh Stout 43:10

They tell a really good story. So he was trying to draw that kind of connections, but it was only after the Renaissance that paintings became important, ie carving has been sidetracked, particularly hard stone carving. When we did carve, we carved in marble, but these hard stones really last better. They're just very difficult to make big. And so people liked big Art became something that you had to make big had to put on a wall and wasn't something that was carved out of jade that you could put in your pocket. But Jade was always seen as sort of the epitome of, of of value and lasting value and of the art that you could carry with you in many, many cultures.

Eric 43:46

From Is the Chinese understanding of jade similar to that?

Dr. Josh Stout 43:50

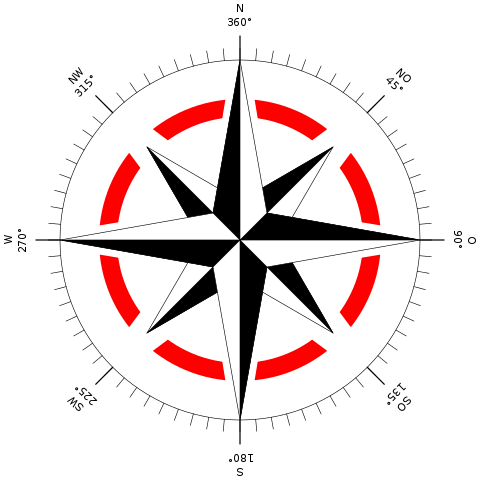

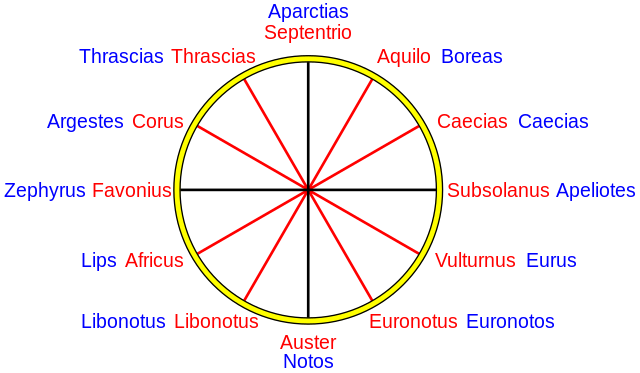

That is the Chinese understanding, but it's also the Mayan understanding that the jade artifacts were the highest thing that you could, you could put to an offering if you broke it, which took a lot of effort, a broken jade axe would be a tremendous sacrifice that you would made. So these these things were were definitely the highest forms of art at the time. So I'm trying to reference these kinds of things in my art, but I'm trying to then relate it to a much longer history, particularly looking at the transition from, say, Neolithic to Bronze Age kind of works, which for me have the most lasting symbols, right? These were the sun symbols come from where the Venus symbols come from. You know, a simply a star looking like a compass. Rose was forever the symbol of Venus or a or a moon. Right. These are these are these are symbols that we understood as integral to who we are as as as humans. And we've carved and painted these things forever. And so this is the kind of stuff that I think we need to become reconnected with both matter and time. And we and I'm trying to do that through my art, but through an understanding of of human evolution and our relationship to to to our own our own history and and time.

Eric 45:08

Fascinating.

Dr. Josh Stout 45:09

Well, thank you.

Eric 45:11

All right. Thank you very much. We'll see you next time.

Dr. Josh Stout 45:14

See you next time.

Wendy Bellermann Arts

Theme Music

Theme music by

sirobosi frawstakwa